I remain appalled at the “content” (or rather, the lack thereof) taught in Georgia’s 8th grade classrooms about the state’s history—and especially the short shrift its deep and rich African-American history receives. Of course, the same can be said for the nation’s classrooms during Black History Month. (Why February? Comedian Chris Rock once said, “Because it’s the shortest month.”) There would be no need for such a thing as Black History Month if African Americans’ story had been told properly and effectively all along, but that didn’t—and hasn’t happened—so here we are.

I remain appalled at the “content” (or rather, the lack thereof) taught in Georgia’s 8th grade classrooms about the state’s history—and especially the short shrift its deep and rich African-American history receives. Of course, the same can be said for the nation’s classrooms during Black History Month. (Why February? Comedian Chris Rock once said, “Because it’s the shortest month.”) There would be no need for such a thing as Black History Month if African Americans’ story had been told properly and effectively all along, but that didn’t—and hasn’t happened—so here we are.

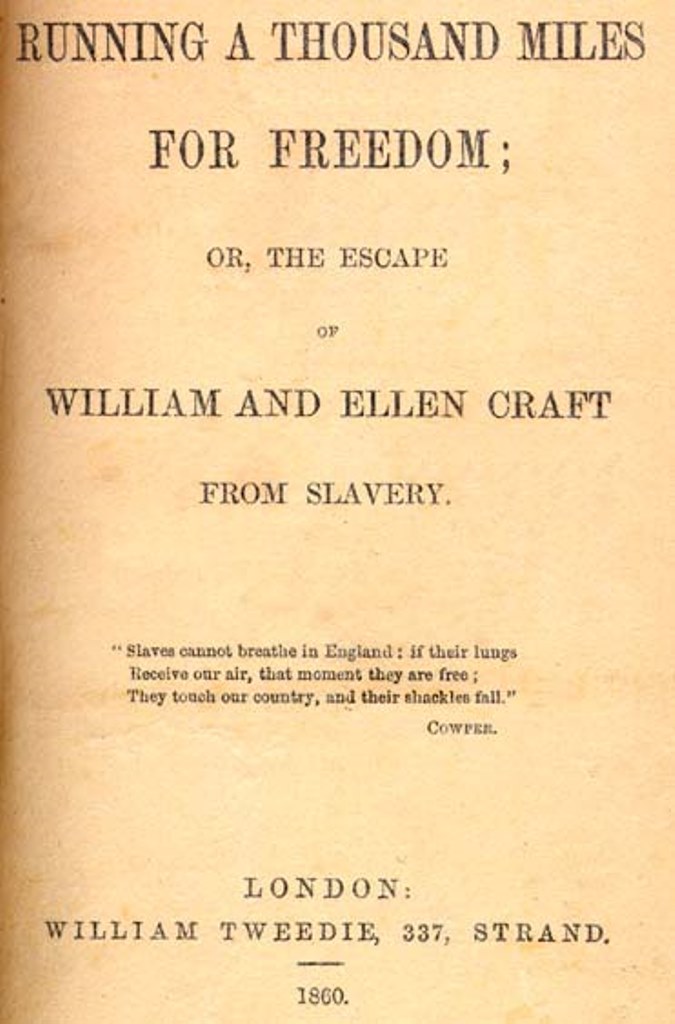

Well, here’s something. When I worked on my father’s book, this story—which I’d never heard before—jumped off the page at me. I was so enthralled by it that I later wrote a screenplay based on the lives of William and Ellen Craft. It was optioned to Hollywood (and hasn’t been heard from since, alas). But it’s a great story—made even better by the fact that William Craft told it himself in Running a Thousand Miles to Freedom. You can download it as a document here. (It’s in the public domain and available on other websites and in several print versions.)

The following passages are excerpted from The Way It Was in the South: The Black Experience in Georgia, by Donald L. Grant (University of Georgia Press, 2001). Copyright Mildred B. Grant. All rights reserved.

The Amazing Story of William and Ellen Craft

The most publicized form of slave resistance was running away, and the good Dr. Cartwright also invented a syndrome to explain that behavior: drapetomania, or in simpler terms, “the disease causing Negroes to run away.”

The slaves’ actions in resisting slavery encouraged the development of the Northern abolition movement. When thousands of the most vigorous, militant slaves left the South, their exodus may have acted as a safety valve, letting off the steam of slave discontent and saving the whole system from explosion. Efforts to downplay slave resistance fail to properly credit this “venting.” In any case, runaways shook the confidence of masters in their ability to maintain and strengthen the system. We will never know the exact number of fugitive slaves because secrecy, not record keeping, was the key to their success.

Most masters were reluctant to admit that their slaves ran away and minimized the number, believing that public discussion of the problem would only encourage more slaves to make a break for freedom. The 1850 census states that Georgia had only eighty-nine fugitive slaves, an incredibly low number. In the next ten years the runaway problem became more acute as the abolition movement matured, but the 1860 census indicated that runaways from Georgia had declined to an absurdly low twenty-three — a total whose accuracy is easily discounted.

Usually the only record left on most runaways was a brief notation in the plantation books that one disappeared. We have few records of what happened to those who were successful. The Talbot County owner of Mabin, a runaway, posted a twenty-dollar reward, but his will noted that Mabin was still unrecovered seven years later. Some escaped slaves, such as John Brown of Georgia, dictated their life stories to abolitionists after they achieved freedom. James Madison, a slave of John T. Snypes, recounted his adventures to Henry Bibb, a black abolitionist. Madison, born in 1827 in Georgia, set off for Canada one day. His owner and a slave catcher caught and manacled him to the back of their buggy and went into a tavern to celebrate. While they were getting drunk, Madison picked the lock of his manacles with a nail and completed his trip to Canada.

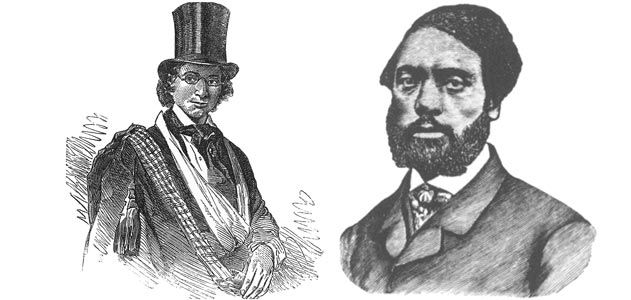

Georgia was powerless to obtain the return of determined slaves who had the support of Northern abolitionists. Two famous runaway slaves played a part in Georgia’s decision to secede from the Union by showing the state it could not prevent such escapes. Ellen Craft was her original master’s daughter and light enough to pass as white. This annoyed her mistress, for it led Ellen to be mistaken for her daughter. When Ellen was eleven, she was given to the mistress’s daughter, Mrs. Robert Collins of Macon, as a wedding present. William Craft belonged to a neighbor.

The Crafts fell in love and were married in a slave ceremony in 1846. Though relatively well treated, they were disturbed by their recent separation from relatives due to sales. William had been trained as a mechanic and carpenter, and his master let him keep a small portion of his earnings. Using his skills, he worked nights and Sundays to accumulate money for the escape. They both applied for a Christmas pass in 1848, claiming they would visit Ellen’s sick aunt. This gave them a head start before they were missed, since their owners would be preoccupied during the holiday.

The Crafts developed a daring plan. Ellen would dress as a young gentleman and pretend to be sick. William, who was much darker, would then pose as her slave coachman, and she would say she was going to a medical specialist in Philadelphia. The plan included three nights on the road. To avoid arousing suspicions, Ellen stayed in the best hotels; her “coachman slave” slept in the stables. Ellen could not write, so the problem of being exposed when asked to sign her name in hotel registers was avoided by putting her right arm in a sling. To complete the masquerade, her face was covered with poultices to add credibility to the story that she was going to see a skin specialist. The plan worked. In Charleston they stayed at the same hotel in which former vice president John C. Calhoun and the governor of South Carolina stayed when they were in the city.

Once across the Mason-Dixon line they were met by William Wells Brown, an escaped slave who had become an active abolitionist writer and lecturer. To Ellen’s dismay, they were first sent to the home of a white abolitionist near Philadelphia for safekeeping. Ellen was suspicious, but she soon realized that fugitives had some true friends among Northern whites. Using Boston as home base, they went on the abolitionist lecture circuit with Brown beginning in January 1849, only a few days after their arrival in the North. They became such drawing cards that sometimes admission was charged, “an almost unprecedented practice in abolitionist circles,” according to Benjamin Quarles.

On learning the Crafts were in Boston, Dr. Collins hired a Macon jailer and a laborer to recapture them. The two men arrived in Boston and obtained warrants for the arrest of the Crafts, but their efforts were thwarted by abolitionists. Shortly after this, on November 7, 1850, Theodore Parker, a white Unitarian minister, “officially” married the Crafts in a solemn ceremony in which he placed a Bible in one of William’s hands and a weapon in the other. The Bible symbolized William’s duty to save his and his wife’s souls. The weapon symbolized his right to defend himself from being returned to slavery. Parker said he had no right to fail to defend his wife from being returned to Georgia even if he had to take a thousand men with him to the grave. Fearful for their safety on American soil, the Crafts went to England and continued their work as prominent abolitionists.

* * *

William and Ellen Craft, Georgia’s most famous runaway slaves, returned from England in 1870 and managed a plantation just across the Georgia line in South Carolina but were burned out by nightriders. They then tried again on the Woodville plantation in Bryan County near Savannah, where they established a school patterned after the Oxham school they had attended in England. They attempted to make Woodville a successful farming operation despite resistance from local white planters. The farm failed following Ellen’s death in 1891, although the school lasted into the next century.

Liked this post? Follow this blog to get more.