January 1965: Georgia House of Representatives refuses to seat Rep.-elect Julian Bond (D-Atlanta) due to his position against the Vietnam War. In Reconstruction Georgia, the legislature expelled all its black members. Both times, the federal government was forced to reinstall democracy in Georgia. Among his constituents: Martin Luther King Jr.

The following excerpt on Bond’s case comes from The Way It Was in the South: The Black Experience in Georgia, by Donald L. Grant, edited by Jonathan Grant. Published by The University of Georgia Press. (All rights reserved). Much of the book was written and researched in a building named after Bond’s father, Horace Mann Bond, onetime president of Fort Valley State College (now University).

The South Georgia legislator railing against “the infamous Mr. Bond” was Bobby Pafford, known for his histrionics, who was later elected to the Public Service Commission. I served as the PSC’s spokesman for several years in the 1980s and got to know him rather well, bless his heart.

* * *

The Georgia General Assembly’s lower house districts were redrawn in 1965, and Atlanta had several new posts in majority-black districts. John Lewis and SNCC workers persuaded Julian Bond to run in the 136th against two other blacks: the Rev. Howard Creecy, a Democrat, and Republican Malcolm Dean, an Atlanta University administrator. Bond energetically hit the streets campaigning for a two-dollar minimum hourly wage, repeal of the state right-to-work law, abolition of the death penalty (when Georgia had the highest execution rate in the country), and other proposals geared for a district with 50 percent male unemployment. Bond took 70 percent of the May 5 primary vote and over 80 percent of the general-election total. Five other blacks had won House seats, and the two black incumbent senators kept theirs. Bond prepared to take his seat on January 10 under the Gold Dome, where he had been ejected in 1961 for trying to integrate the visitors’ gallery. The twenty-five-year-old freshman was blissfully unaware that the state assembly would react to his antiwar sentiments with one of its most drastically repressive acts since the ouster of all black legislators in 1868.

In November, SNCC drew up a position paper opposing the war in Vietnam. On January 6, SNCC publicly suggested that potential military draftees should be allowed the alternative of civil rights work–to fight for democracy in the United States rather than fight for an undemocratic Asian regime. When news spread that SNCC member Bond agreed with that position, all hell broke loose for him. Pro-war patriotism played well politically in Georgia then. Most blacks disagreed with Bond’s position, for that matter. Although blacks sat in the legislature, they were supposed to “behave themselves,” not speak out. The local media sensationalized the story and goaded politicians to react.

Bond became the victim of accumulated white resentment against the gains made by the civil rights movement over the past four years. White legislators felt a need to strike back at a genuine civil rights activist. Even moderates wanted Bond to apologize and recant in order to take his seat. “This boy has got to come before us humbly, recant and just plain beg a little,” privately explained one legislator. Bond could not and would not do this. When the legislature convened, a group led by James “Sloppy” Floyd moved to deny Bond his seat. One South Georgia lawmaker, a leader of the rural bloc, was practically in tears as he declared,

Blood runs down the trenches in a far-off land, causing tears to run down widows’ cheeks and husbands’ and children’s faces. . . . The legislature has been invaded by one whose thinking pursues not freedom for us but victory for our enemies . . . . The infamous Mr. Bond.

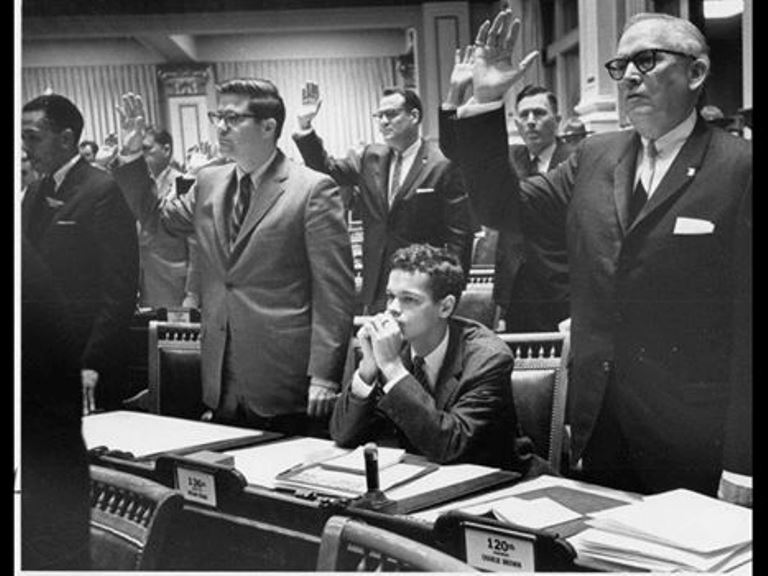

As sole judge of the fitness of its members, the legislators voted to refuse Bond his seat on opening day, 184-12. Five black representatives and seven whites from metro Atlanta supported him. Although Bond’s treatment was reminiscent of that accorded Georgia’s black legislators in 1868, white lawmakers claimed their action was not racially motivated.

Bond became a cause célèbre. Over the objections of Atlanta NAACP President Samuel Williams, one thousand SCLC and SNCC protesters, led by King, marched to the Capitol to object to Bond’s expulsion. Dr. Williams wanted to do the impossible and keep civil rights and Vietnam issues separate. Meanwhile, Bond’s case went to court. The U. S. District Court’s ruling against Bond was appealed to the Supreme Court, which ruled unanimously in Bond v. Floyd on December 5, 1966, that Bond had to be seated. In the meantime, Bond won two special elections called to fill the “vacancy” from his district. He also went on a national speaking tour. One year after he was denied admission, he took his seat at the Capitol.

Liked this post? Follow this blog to get more.