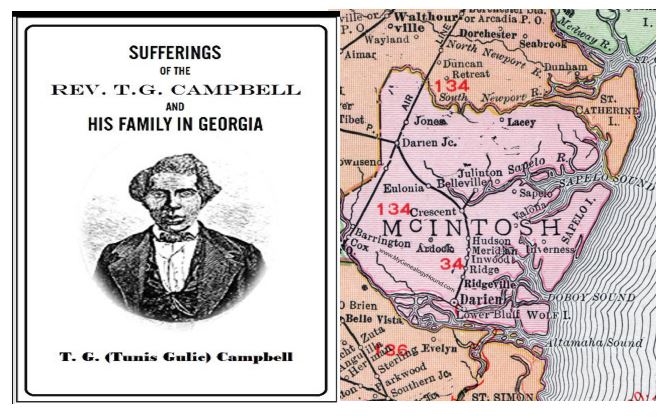

Tunis G. Campbell, Sr.

Georgia Black Reconstruction Leader

By Jonathan Grant

@Brambleman

In 1861, a 49-year-old black abolitionist named Tunis G. Campbell, Sr., walked into a recruiter’s office in New York City and attempted to enlist in the Union Army. Like all African-Americans in the war’s early stages, he was rejected as unfit on the basis of his race.

Campbell, a well-educated restaurateur, baker, and published author, didn’t give up. He wrote a letter to President Lincoln outlining a self-improvement plan for freed slaves after the war. As a result, he was sent to Union-occupied Hilton Head, S.C., to work with General Rufus Saxton.

In 1865, Campbell—a tall, imposing man who dressed formally and wore spectacles—was appointed military governor of five Georgia sea islands. He founded a school for freed people and moved to implement Sherman’s famous order distributing lands to former slaves—the historical basis for the broken promise of “Forty Acres and a Mule.”

In 1867, he and his followers were driven off the islands by Union troops following a change in federal policy, when President Andrew Johnson granted amnesty to white Confederate planters and restored their lands to them.

Proud, militant, and undaunted, Campbell purchased a plantation in rural McIntosh County. Its county seat, Darien, had been burned by black troops during the war and racial animosities were high. Blacks outnumbered whites 4-to-1 however, and when Georgia underwent Congressional Reconstruction, Campbell became a political power to be reckoned with—as a voter registrar, constitutional convention delegate, and one of three state senators elected in 1868 (the highest ranking black elected officials in state government until the 1980s).

Overall, Georgia had the nastiest Reconstruction experience of any state—often considered as violent as the war itself. The original Ku Klux Klan, functioning as the military arm of the Democratic Party, rode roughshod over black voting rights—but the Klan didn’t set foot in McIntosh County, where Campbell had formed a black militia.

In Atlanta, Georgia’s black legislators soon fell victim to a monstrous injustice. White legislators, including the black legislators’ so-called Republican allies, made it their first order of business to throw out the black lawmakers. White leaders disingenuously declared that while blacks could vote, they could not hold office. Campbell and others, notably the eloquent Henry McNeal Turner and the outrageously flamboyant A.A. Bradley, vainly fought their ouster.

Campbell kept on fighting, traveling to Washington, D.C., to confer with Sen. Charles Sumner about the outrages in Georgia. These meetings bore fruit: There were hearing on the Ku Klux Klan atrocities, and ultimately the federal government forced Georgia to seat its duly elected black legislators. This time, Campbell fought to keep former Rebels from taking their seats.

Political terrorism continued, however, along with massive election fraud. Black politicians were threatened, beaten, and even murdered. Campbell was subsequently defrauded of his Senate in a rigged election, but he managed to remain an elected justice of the peace in McIntosh County, where he continued to uphold the rights of black citizens, much to the chagrin of whites. His refusal to back down meant that his enemies would try to destroy him.

In 1876, he was prosecuted for abuse of office after he levied a $50 fine on a white man. His arrest was marked by riots, and Campbell was hauled into a white judge’s courtroom, where he was not allowed to present a defense. He was convicted and sentenced to two years as a leased convict, a common fate for blacks. A man who had always been free was reduced to slavery.

In 1876, he was prosecuted for abuse of office after he levied a $50 fine on a white man. His arrest was marked by riots, and Campbell was hauled into a white judge’s courtroom, where he was not allowed to present a defense. He was convicted and sentenced to two years as a leased convict, a common fate for blacks. A man who had always been free was reduced to slavery.

After his release, he briefly returned to McIntosh County, where adoring blacks listened to him speak against the whites’ hand-picked black legislative candidate. Campbell’s man won the election handily. And then he left the scene of his triumphs and despairs. He spent his last years as a missionary for the African Methodist Episcopal Church in Boston. He wrote a book, Sufferings of the Reverend T.G. Campbell and His Family in Georgia, published in 1877. He died in Boston in 1891.

The political foundation Campbell built lived after him. By 1900, Georgia’s only black legislator was from Campbell’s old stronghold. William Rogers was unseated only after whites voted to change the state Constitution in 1908 to completely strip blacks of the right to vote or hold office.

Suggested reading:

The Way it Was in the South: The Black Experience in Georgia, by Donald L. Grant and Jonathan Grant (UGA Press). Link

Freedom’s Shore: Tunis Campbell and the Georgia Freedmen, by Russell Duncan (out of print)

“Campbell, Tunis Gulic,” by Donald L. Grant. Dictionary of Georgia Biography (out of print)

“Grit and Gumption in Gullah Country: Tunis Gulic Campbell (1812–1891),” by William “Duke” Smither. Link

Liked this post? Follow this blog to get more.