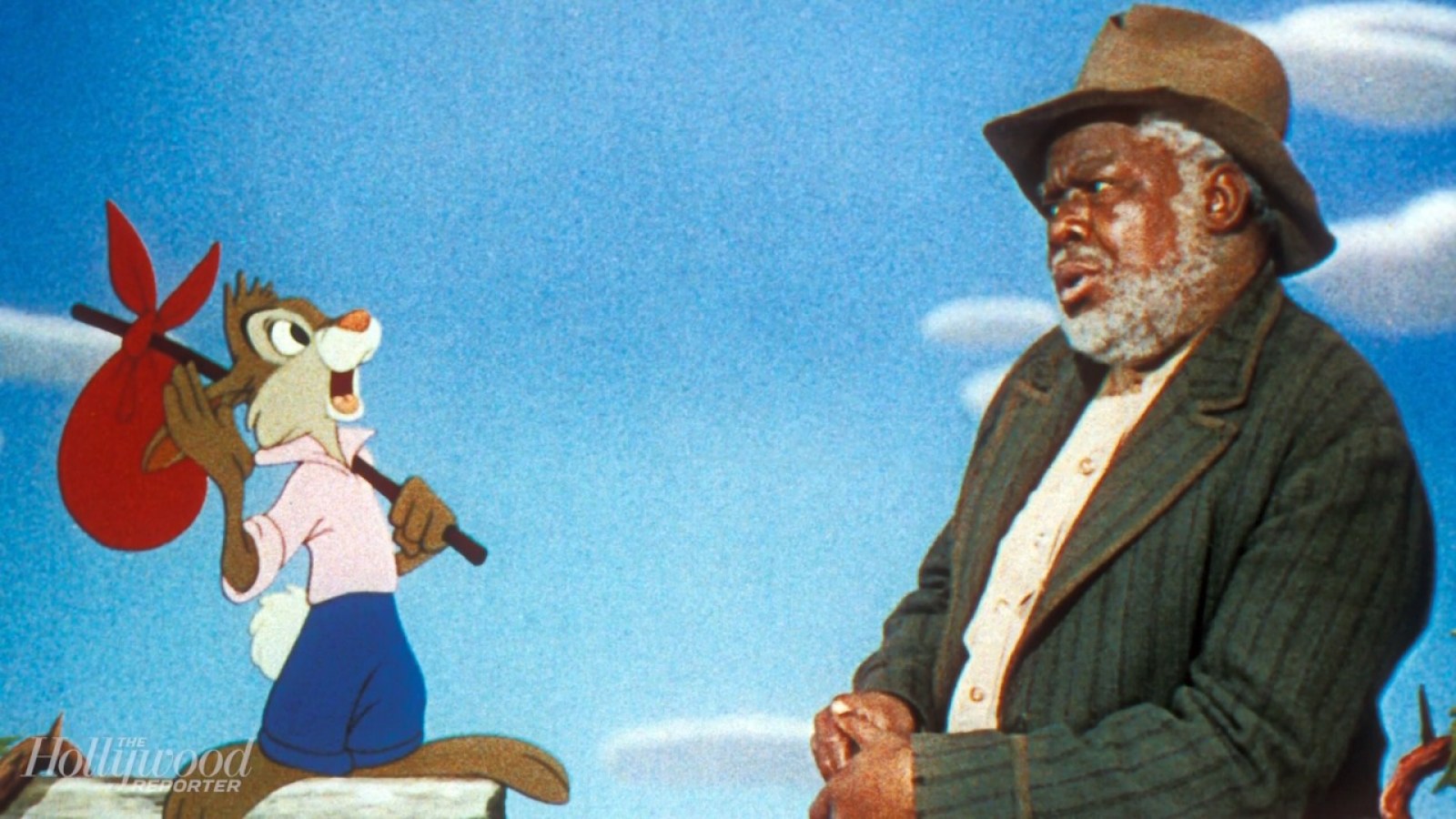

Above: Still shot from Disney’s Song of the South (1946), a racially problematic movie removed from the marketplace due to stereotypical depictions of African-Americans and romantic depiction of plantation life. Like the movie’s Uncle Remus, Matthew Lieberman’s Lucius is a so-called “Magical Negro” who can communicate with animals.

The slave is imaginary. The problem is real.

By Jonathan Grant

@Brambleman

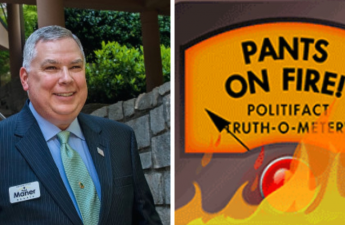

In 2018, Democratic Senate candidate Matt Lieberman self-published a novel. It was little noticed until late last week, when Huffpost ran an article calling Lucius “deeply bizarre” and “filled with racist tropes.” The negative publicity has increased calls for Lieberman, widely considered a spoiler candidate, to drop out of the the race in favor of the party establishment’s preferred candidate, Raphael Warnock.

Warnock is Black, the pastor of Atlanta’s famed Ebenezer Baptist Church. Lieberman is White, the son of former U.S. Sen. Joe Lieberman, a former vice-presidential candidate who has a less than perfect record as a Democrat. Both Warnock and the younger Lieberman are political novices, but they’re the top-polling Democrats among more than 20 candidates in the Nov. 3 special election for the remainder of Johnny Isakson’s term. Kelly Loeffler, herself a novice appointed by Gov. Brian Kemp, currently holds the seat and plans to spend $20 million of her own money to keep it.

With so many candidates, including GOP Rep. Doug Collins, we’re almost certain to see a January runoff between the top two finishers, with one of them being Loeffler or Collins. While polling is early and results are inconsistent, so far Democrats have been split between Lieberman and Warnock, with former State Sen. Ed Tarver lagging behind. This causes indigestion for Team Blue. If Collins and Loeffler both make the runoff, Democrats will cry and moan and hate themselves and each other, but especially Lieberman. Hey, no one said any of this was fair. Did I mention Loeffler is dropping $20 million into the race?

Playing defense, Lieberman rejects the criticism of Lucius, telling Huffpost that the novel is “an honest examination of enduring racism against Blacks—which is real, harmful and totally infuriating.”

Wanting to see what the ruckus was about, I read Lucius. Being involved in politics, and having written a few novels, two of them self-published (including Brambleman), as well as co-authoring and editing The Way It Was in the South: The Black Experience in Georgia, I decided to share some thoughts on the book.

About the book

A short novel at just over 200 pages, Lucius is really more of a long novella, given the small number of characters and the simple plot line. Lieberman says he wrote Lucius in the aftermath of the August 2017 “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia. He published it five months later. This is a short time frame to write and publish a book.

In the AJC’s Jolt, one Insider (I’m guessing Jim Galloway) wrote: “The red flag here is ‘self-published.’ Editors exist for a reason.” True, but being independently published doesn’t mean it wasn’t edited (I use outside editors, and I am one). The lack of an Acknowledgements page strongly suggests that Lieberman neither used an editor nor workshopped the story in a writer’s group, another way to avoid the pitfalls of publishing one’s work spaghetti-on-the-wall style. I assume Lieberman had no idea he’d be running for the U.S. Senate when he wrote Lucius. Now that he is, the lack of vetting of his work is coming back to bite him.

While I don’t believe for a minute that Lieberman is indifferent to racism, he hasn’t made fighting it a cornerstone of his campaign. His tweets show standard Democratic sensibilities, and his website touts a philanthropic record of helping marginalized communities, but it doesn’t address racism directly, although he supports a new Voting Rights Act.

That being said, Lieberman’s claim that Lucius is an honest attempt to deal with racism is balderdash, to put it mildly.

A Bojangles vibe and troublesome tropes

Lucius tells the tale of ninety-year-old Benno Johnson, a wealthy White Atlantan who claims he owned a slave named Lucius for eight decades, until Lucius’s death in 2017. The novel’s first-person narrator is Tree Weissman, a volunteer lay leader of sabbath services at a Jewish retirement community. After a service one day, Weissman meets Johnson, who’s not Jewish but lives in the community. During a casual conversation, Johnson mentions his slaveowner status and offers to tell Weissman more, believing that this is a story he should tell. Weissman is game, and in a series of meetings, the old man recounts his relationship with Lucius, purportedly given to him by his well-to-do parents when he was a child in the 1930s. Bear in mind Johnson appears lucid in all respects, and his account goes largely unchallenged by Weissman, who plays the role of a largely passive stenographer.

Lucius speaks in dialect, which gives the narrative a Bojangles vibe that will put off many readers. Lucius also has the ability to communicate with animals, a power he can pass on to Johnson. The Huffpost article called this “a textbook example of the magical Negro trope, in which Black characters are portrayed as vessels for wisdom or supernatural powers that can provide enlightenment or aid to white protagonists.” It’s a troublesome conceit to use in a story. That the term “magical Negro” was popularized by film director Spike Lee says a lot about it.

Despite the fantastical nature of Johnson’s tale, Lieberman leaves the matter of Lucius’s existence open to dispute. The narrator has a brief conversation with a staff doctor at the retirement home (which would violate patient confidentiality, of course). The doctor says that Johnson is basically mentally sound and calls Lucius’s existence “doubtful but not impossible.” Weissman never takes any further steps to resolve the issue. I found the narrator’s incuriosity on this issue striking, since slavery in various forms exists to this day.

After that, the story is simply Johnson holding forth. He calls Lucius his friend, but treats him like a dog. He recounts regular abuse and mistreatment, calling Lucius “boy,” forcing him to sleep on a floor pallet (into his 80s!), feeding him scraps, leaving him uneducated, and forcing him to wait outside when “massa” eats in a restaurant or goes to his country club. Nevertheless, Lucius is said to be happy and content, and he is filled with primitive wisdom and helpfulness for his White master that you’d expect a magical Negro to have.

At one point, Lucius breaks out singing Stephen Foster’s minstrel song, “Swanee River.” Lieberman thoughtfully includes the complete lyrics, which recount a slave’s longing for his old plantation home. (BTW, it’s now Florida’s state song, although “plantation” has been replaced by “childhood station.”)

The most troubling aspect of the book is the free ride the narrator gives Johnson. Despite his casual, cruel, and constant racism, Johnson is treated as a sympathetic character, popular with the other residents. His attitudes remain unchallenged by Weissman even as he nonchalantly describes his inhumanity to his constant companion and “friend.”

Much of the book is devoted to an ill-fated canoe trip Johnson and Lucius take down the Chattahoochee in 2014, when both men are in their late 80s. The logistics of the river trip are nonsensical, but somehow they end up at a White Supremacist rally, complete with torches. Johnson shares some Trumplike views toward the Klan: “I’ve know a number of folks over the course of my life who were Klan, and they were basically good people … I never really held it against them.” Since the story takes place in 2017, he’s saying this three years after the “good people” in his account form a mob and chase the octogenarian Lucius into a swamp.

Near the end of the book, residents gather to hear Johnson’s account of Lucius’s final hours. They weep when they learn he was killed by a bow hunter as he ran with a herd of deer. “We were deer,” Johnson says, “and he was allowed to hunt us. You’re not allowed to use a gun to hunt around here, near the city; that would be illegal. But a crossbow is fine. So it was all legal.”

No, it wasn’t. According to Johnson, Lucius was killed Aug. 16. Georgia’s bow hunting season doesn’t start until September–a fact that isn’t pointed out in the story. (Editors exist for a reason!) Sadly, Lucius couldn’t catch a break. No justice. I mean, if he’d really loved Lucius, Johnson would have at least checked to see if he’d been killed out of season.

Why didn’t Johnson free Lucius? The issue comes up between the two of them on the eve of Lucius’s death. Looking back, Johnson recounts a conversation with his bondsman in which he considers freeing Lucius. (One of slavery’s many cruelties was the master’s emancipation of slaves when they were too old or feeble to fend for themselves, but this isn’t mentioned in the book.) According to Johnson, Lucius tells him, “I been free pretty much all along,” a statement that serves mainly to justify Johnson’s actions, even if they are only in his mind.

There is no real sense of history–Lieberman mumbles his way through it, to the extent he touches on it at all–and there are no significant Black characters in the story other than the dehumanized Lucius; Johnson speaks for him in a “des-dem-dose” dialect. The only other Blacks are aides in the retirement home, extras put in the story to serve Johnson.

This passage is telling:

Benno’s description of the Klan as half respectable made me cringe, and I noticed it also caught the attention of one of the Black aides who was within earshot, which made me cringe a little more. I figured she’d cut Benno some slack as a resident and an old man; that’s the world he came up in. Whether she extended the same slack to me, his audience, I couldn’t say.

Weissman couldn’t say because he didn’t ask, which is another missed opportunity–one of so very, very many–to get a different point of view. One way would have been to have a Black psychiatrist as the narrator. That would have made it a completely different book, of course. Having no authentic African-American voices is a fatal flaw. It’s also laughable, reminiscent of Jim Crow-era conferences on race relations when white people gathered and talked amongst themselves about “the Negro Problem,” with no Blacks invited.

I kept hoping a Black woman would say, “That old man does NOT know what he is talking about.” Nope. The White man’s self-serving narrative remained uncontradicted. Nothing new in that.

There have, of course, been great novels about racists written by Whites, like Paris Trout. In that case, there’s a reckoning as the community reaps the whirlwind. In Lucius, however, there is no epiphany, no redemption, no reckoning, no whirlwind. Johnson doesn’t break off his narrative, look around, suddenly ashamed of a grievous lifelong sin. Instead, Johnson is rewarded in a classic comic ending: a marriage bed, because he’s a charming and lovable rascal.

Beyond tone deafness

Johnson’s consequence-free racism is beyond tone-deaf. Lieberman claimed that it’s an “honest examination of enduring racism.” Not so much. There’s an emptiness to the narrative, a complete lack of context. This is worse than regrettable. It’s bewildering and unconscionable.

It can also be seen as an effort to downplay the importance of slavery–something that’s been going on for a long, long time. However, it was certainly raging at the time Lucius came out, as well as today. Many Americans erroneously believe slavery was not the main cause of the Civil War. While Lieberman was writing Lucius, The Washington Post reported: “a McClatchy-Marist poll asked ‘Was slavery the main reason for the Civil War, or not?’ Just over half (53 percent) said it was, while 41 percent said it was not. Among Republicans, opinion was more narrowly divided: 49 percent yes and 45 percent no.”

The narrator preaches a kind of color-blindness, but there’s an unwillingness to dig deeper. Unfortunately for Lieberman, he patterned Weissman’s character after himself, which shows a lack of imagination and effort. He also makes Johnson a former resident of Weissman’s street, on the bank of the Chattahoochee; much of the story occurs on the river and its swamps. This unwillingness to step outside his comfort zone has created a discomfiting result.

No doubt Lieberman would like the issue to go away. He issued a statement in response to the Huffpost article, but hasn’t posted it anywhere that I’ve seen. Nor has he tweeted about it. (His current Twitter account was set up around the time he decided to run for Senate.)

In dismissing the uproar and rejecting criticism, Lieberman pointed to a Kirkus review praising the book’s “artistic and philosophic depth.” Here’s the thing: You you can buy yourself a Kirkus review for $425, which no doubt he did. I can find no other published reviews, but I do see signs he didn’t push the book much: On Goodreads, only three reviews, one by a Lieberman.

But on Amazon, 4.9 stars! Astronomical ratings with few reviews (only nine in this case) are a sign of home cooking. While one reviewer (see above) is also a contributor to Lieberman’s campaign, his review is much more generous than his political donation. It also contains no indication that he actually read the book, which he calls “Lucious.”

In the end, this is an unserious effort, the work of a dilettante. And now he’s dabbling at the high end of politics, his book’s message hangs in the air like a malignant odor.

It’s a privilege to write a book like Lucius. And I don’t mean that in a good way.

Disclosure: I plan to vote for Raphael Warnock

Liked this post? Follow this blog to get more.

I just finished reading a lengthy summary of his vile book on huffpost and barely finished reading yours. It literally makes me sick to the stomach to know such a book could be written in 2020. Matt Lieberman is in full damage control and he’s finished.

Like the accomplice in the Ahmaud Arbery murder, who shows up on CNN sporting an imbecilic bowl haircut while his lawyer portrays him as an uneducated country boy, Matt’s Lieberman hopes he will at least get a pass for being a white man clueless about race relations like his Benno character, if he fails to spin his book as an allegorical response to the Unite the Right Rally in Virginia.

A well-educated, Jewish man who is son of a US senate is indeed a very privileged position to be in. It makes Lieberman all the more despicable. Even the most vile, hateful racist would see him as one of their own, not as a naive man who badly fumbled an anti-racist book. Lieberman failed to give any serious contemplation to his book, especially being a member of a group who experienced a recent holocaust. In reality, he is wrote the book to feast himself on ugly fantasies of dehumanization and subjugation of another racial group to strengthen quell his demons inner demons of power and insecurity. Clearly, he’s unfit for public office.