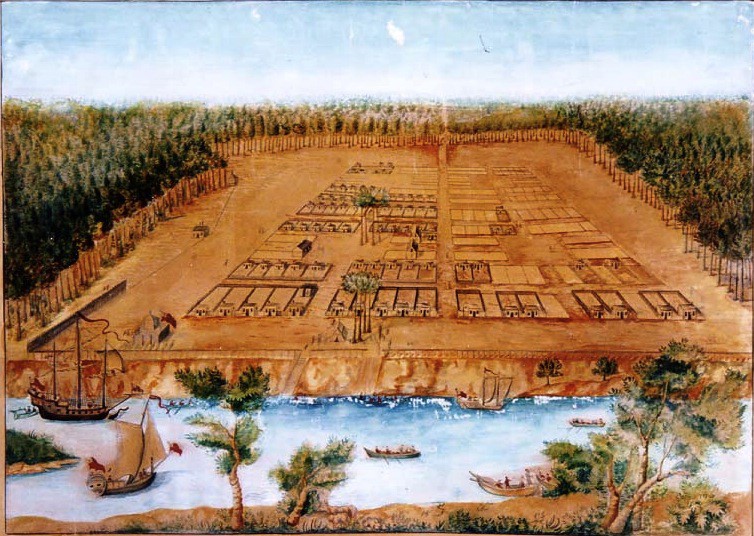

Above: Early layout of Savannah

This is an excerpt from The Way It Was in the South: The Black Experience in Georgia, by Donald L. Grant. Available from University of Georgia Press.

About the book

At the age of 52, my father received his PhD in History from the University of Missouri and accepted a position at Fort Valley State College (now University), a public HBCU in Middle Georgia south of Macon. Throughout his tenure and beyond, he worked on what turned into a monumental history of Black Georgians. Unfortunately, he died in 1988 without getting it published. After his death, I reviewed his work. Recognizing its value, I editing the massive 1,500-page manuscript down to publishable length and extended the narrative’s timeline into the 1990s. (That turned into a story in and of itself.) Fortunately, there was a good deal of interest in the book and it was originally published in hardcover in 1993. It received a good deal of critical acclaim and received Georgia’s nonfiction “Book of the Year” award in 1994. It was later published in paperback by the University of Georgia.

At the age of 52, my father received his PhD in History from the University of Missouri and accepted a position at Fort Valley State College (now University), a public HBCU in Middle Georgia south of Macon. Throughout his tenure and beyond, he worked on what turned into a monumental history of Black Georgians. Unfortunately, he died in 1988 without getting it published. After his death, I reviewed his work. Recognizing its value, I editing the massive 1,500-page manuscript down to publishable length and extended the narrative’s timeline into the 1990s. (That turned into a story in and of itself.) Fortunately, there was a good deal of interest in the book and it was originally published in hardcover in 1993. It received a good deal of critical acclaim and received Georgia’s nonfiction “Book of the Year” award in 1994. It was later published in paperback by the University of Georgia.

Chapter One

The Formation of Georgia

Part 1: Beginnings of Evil, or An English Experiment Gone Awry

The history of Blacks in Georgia began long before their enslavement by British colonists. Blacks were intimately involved in the Spanish exploration and conquest of the New World from the beginning. One, Pedro Nuñez, was a pilot for Columbus. Cortez, Balboa, and Pizarro also had significant contingents of blacks. It is likely that most, if not all, of the several Spanish expeditions to what is now the South Atlantic Coast of the United States had Blacks in their ranks.

The first of these expeditions, that of Juan Ponce de Leon, governor of Puerto Rico, discovered Florida for the Spanish in 1512. Thereafter the Spanish restlessly probed northward from their bases in the Caribbean. On April 14, 1528, Pánfilo de Narváez landed near Tampa Bay and from there marched north and west for ten weeks, arriving back on the coast near Tallahassee on June 25. One of the scouts for this five hundred-man Spanish expedition was a Black named Esteban de Dorantes, affectionately called Estevanico, or “Little Steven,” and he may have been the first Black to set foot on what is now the soil of Georgia. After Narváez, the De Soto expedition established a base at St. Augustine, Florida, and visited Georgia in 1540. De Soto left a cannon with the Indians near what is now Macon after demonstrating its power by toppling a tree with a well-placed shot. In the 1550s, the Spanish ventured into Georgia on hearing rumors from the Indians of gold deposits in what is now Lumpkin County, near Dahlonega. These developments eventually led to the creation of the first Spanish settlement in Georgia, when a base was established on St. Catherines Island by an expedition from St. Augustine.

The Spanish hold on Georgia and the Carolinas was tenuous at best. The area was on the outer fringes of Spain’s empire. Repeated efforts to find wealth there proved disappointing, and since Spanish efforts elsewhere in the New World were paying off handsomely, these northern outposts drew little interest and attention. When Georgia was included in the grant of Charles II of England to the eight Lords Proprietors in 1663, the Spanish took little note of the event. By 1686, the Spanish abandoned their Georgia missions and presidios because of trouble with the English, Indians, and pirates.

# # #

The youngest of the original thirteen British colonies began with an official ban on slavery. This prohibition was not instituted out of any respect for the rights of Africans, however. The compelling reasons for the ban were military and economic, not moral. The experiment was never successful, and within twenty years of the fledgling colony’s founding, slavery was officially sanctioned with a shrug of the shoulders by Georgia’s Trustees.

The youngest of the original thirteen British colonies began with an official ban on slavery. This prohibition was not instituted out of any respect for the rights of Africans, however. The compelling reasons for the ban were military and economic, not moral. The experiment was never successful, and within twenty years of the fledgling colony’s founding, slavery was officially sanctioned with a shrug of the shoulders by Georgia’s Trustees.

Before James Edward Oglethorpe founded Georgia in 1733, the British were interested in extending their control of North America south from Virginia and the Carolinas. In 1716, they established a fort on the Savannah River, and from 1721 through 1727 they maintained Fort George on the Altamaha River near what is now Darien as a defense against the French. By 1730, British influence was sufficient to bring an acknowledgment from the Cherokees of British supremacy in this area.

The British wanted to settle Georgia for several reasons. They needed a buffer between the English Carolinas and the Spanish in Florida, partly to resist possible future Spanish claims and to help secure the frontier against Indians but more importantly because Florida was already a haven for runaway slaves who fled the Carolinas and passed through Georgia on their way to safety in St. Augustine. The Spanish encouraged runaways as a tactic in their struggle against the British. In 1699, a Spanish decree promised protection “to all Negro deserters from the English who fled to St. Augustine and became Catholics.” One English sea captain was discomfited when he chanced upon two of these runaway slaves while in St. Augustine. They made faces and laughed at him, secure in the knowledge that the Spanish would do nothing to help an Englishman.

The British moved tentatively to establish the buffer colony of Georgia in 1716 when the Carolina Proprietors granted land between the Savannah and Altamaha rivers to Sir Robert Montgomery; however, his proposed Margravate of Azila — a grand scheme for a feudal colony — failed to materialize. In 1729, title to the area was surrendered back to the king by the Proprietors. Three years later, Oglethorpe and a score of his associates secured a charter for the region between the two rivers, with the charter extending all the way from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific.

The philanthropic nature of Oglethorpe’s colony as a haven for the poor and oppressed — and as a chance for prisoners to make a fresh start — has been greatly exaggerated. Although sermons delivered to annual meetings of the Georgia Trustees opposed the concept of man merely as an economic being, business motives were uppermost in the minds of Trustees and colonists. They saw Georgia as a money-making agricultural venture. Crops would be produced and sold by the corporation the Trustees directed. The imprisoned debtors who came to Georgia to start life anew did not number over a dozen, but the Trustees used this appealing concept to raise funds.

The theory that Oglethorpe founded Georgia as a philanthropic and eleemosynary colony had been encouraged by the fact that Oglethorpe tried to exclude both slaves and liquor at the beginning. There were, however, economic and strategic motives for this. Since Georgia would be a buffer protecting the Carolinas from the Spanish to the south and the French and Indians to the west, a compactly developed settlement of sober, hardworking White Protestant Englishmen was considered the best way to meet this strategic need. Therefore, no individual grants of over five hundred acres were to be made, and only Protestants were allowed religious freedom in the new colony.

Georgia was the only British colony that made an attempt to prohibit slavery. If settlers were to be sturdy yeomen, they should not have slaves — that would induce idleness among the settlers and make work seem degrading. Also, if the English were to defend the area effectively, they should have only small farms in a tight pattern. Small farms would not justify the expense of slave labor. Another reason the Trustees tried to exclude slavery was the logical belief that Black slaves would cooperate with the Indians and Spanish in attacks on the English colonies and would not only escape to Spanish Florida themselves but would also help and encourage the slaves in South Carolina to do so. The Trustees also said slavery was “against Gospel as well as the fundamental law of England,” but they would change their minds about this.

In addition, the Trustees originally anticipated that silk and wine production would be the mainstay of the Georgian economy. They saw these occupations as requiring more skill than strength, and therefore not compatible with slave labor. As with succeeding generations of Whites, they ignored or were ignorant of the high levels of craftsmanship that had existed in Africa for centuries.

The Trustees’ original charter said unequivocally that any kind of slavery, Black or otherwise, was forbidden and that all in the new colony who shall

inhabit or reside within our said province, shall be and hereby are declared to be free. . . . that all and every person which shall happen to be born within the said province, and every (one) of their children and posterity, shall have and enjoy all the liberties, franchises, and immunities of free denizens and natural born subjects . . . as if abiding and born within this our Kingdom of Great Britain. . . .

Which did not mean the Trustees intended for Blacks to have the status of free Englishmen. They made this clear by stating in their original prohibition against slavery that it was forbidden “to hire, lodge, board, or employ within the limits of the province any Black or Negro.

Oglethorpe had no moral or personal scruples against slavery, however. He owned slaves in the Carolinas and was a deputy governor of the Royal African Company, founded in 1672 to win for England a larger share of the slave trade between West Africa and the New World. By the time it was dissolved in 1752, the company had transported 100,000 Africans to New World slavery. The Trustees’ support of slavery outside of Georgia was further indicated by their promise to return to their owners any runaway slaves found in Georgia.

The Trustees recruited settlers with extravagant promises of prosperity if they went to Georgia: All one had to do was “scratch the earth . . . [and] cover the seed in order to be rewarded with unbelievably large yields.” The first settlers sent from England by Oglethorpe’s company arrived at Yamacraw Bluff, now part of Savannah, on February 12, 1733. They were small businessmen, tradesmen, and unemployed laborers. There were no released convicts in the group. Oglethorpe returned to England the following year to enlist more support for the fledgling colony and for the ban on slavery. Back in England, he told the London Trustees: “I have brought all our people to desire the prohibition of negroes and rum.” An act of Parliament had been passed June 24, 1735, entitled “An Act for rendering the colony of Georgia more defensible by prohibiting the importation and use of Black slaves or (free) negroes into the same.” Violations of this act would draw a fine of fifty pounds; the law also provided for the confiscation and sale outside the colony of any slaves who might be there. This showed that Oglethorpe had renewed his determination that Georgia would not follow the Carolina model of a tiny planter elite supported by slave labor. He also reaffirmed the Trustees’ ban on hard liquor and continued to try to limit land grants to create a society of White yeoman farmers.

Oglethorpe, the Trustees, and Parliament might make pronouncements, issue regulations, and enact legislation, but that did not mean Georgia’s White settlers would abide by them. As often happened, when the mother country’s rules interfered with the profits of the colonists, the rules were flouted. Actually, settlers in Carolina moved across the Savannah River with their slaves even before Savannah was founded. Within days of Oglethorpe’s landing, Col. William Bull brought four Black sawyers from Carolina to do the heaviest work building Savannah’s first houses. More slaves were used to to work on roads. Oglethorpe sent them back to Carolina when their work was done and hoped that the new rules would keep all other Blacks from the colony.

However, the law’s enforcement was lax, and the punishment was only a fine. Settlers circumvented the letter of the law from the very beginning by leasing slaves from Carolina for periods of up to a hundred years. The price of the lease equaled the sale price of the slave, and when they spoke of “leasing,” all parties understood it was a euphemism for slavery. The courts closed their eyes to the practice, and in rare cases where it was challenged, the slave was sent back to Carolina as a “runaway,” and the “lessee” was reimbursed by the Carolina “owner.” This clever arrangement ensured that no one dealing in slaves would be financially hurt if the laws and regulations were enforced.

When Oglethorpe returned from England in 1736 with more settlers, he found both slaves and rum being smuggled in from South Carolina and a movement among many of the settlers to make this contraband fully legal. In the 1730s, slaves were widely used in the Augusta region, and there is no record of any legal prosecution. By 1740, there were many complaints by Whites around Augusta that the widespread use of slaves made it difficult for Whites to find employment. One informant of the Trustees estimated there were a hundred slaves in Augusta in 1740, and Thomas Causton, one of the settlers, wrote the Trustees in 1741 that around Augusta the ban was largely ignored. The Trustees took no action on this information.

Oglethorpe and the Trustees not only had these individual acts of defiance to deal with: They also faced a rapidly growing organized resistance. In 1735, seventeen residents of Savannah petitioned the Trustees for the “use of negroes” on the spurious grounds that “their constitutions are much stronger than White people’s.” The freeholders found that White indentured servants were unwilling to work for no pay and were leaving before their terms of indenture had expired. South Carolina’s failure to return runaway White indentured servants increased the pressure for the introduction of Black slaves into Georgia. Georgia officials had been active in seeking to return South Carolina’s fugitive slaves who escaped to Georgia and resented the lack of reciprocity.

In 1738, 117 freeholders, led by Patrick Tailfer, a lowland Scot, petitioned for the introduction of Black slaves and complained they had been tricked by the Trustees into believing they would earn six times as much in Georgia as in London. The Trustees rejected the request six months later on the grounds that other Georgia settlements had petitioned for the maintenance of the ban against slavery because they believed that slavery would create an aristocracy and drive out the poor Whites needed to defend the colony against the Spanish and Indians.

The Trustees might deny petitions, but they could not stop the influx of slaves or prevail upon local officials to support the ban. One example of the refusal of local authorities to support the exclusion of Blacks from Georgia occurred in 1737 when Captain Davis, a Savannah merchant, fired his ship’s captain because the man had mistreated Davis’s Black mistress/administrative assistant. The discharged captain took the case to court, but the court did not question the Black woman’s right to live in Savannah.

By 1740, pro-slavery pressures were mounting. The majority of Trustees reaffirmed the ban even though the lack of slaves was cited by the settlers on the Ogeechee River as the reason they abandoned their lands. Part of the Trustees’ stand was based on the fear of slave insurrections. South Carolina had recently experienced several slave revolts, including the 1739 Stono Revolt in which eighty slaves burned several buildings and killed twenty-five whites before they were defeated in a pitched battle by the better-armed White militia. The following year, fifty slaves were hanged in Charleston for insurrection, and the entire colony was on the verge of hysteria. Oglethorpe and the Trustees felt that conditions in Georgia would be even more conducive to slave revolts if many slaves were brought into the colony.

The petitioning freeholders were not impressed with the authorities’ reasoning and in August 1740 repeated that they still wanted slaves, claiming they thought only slave labor would guarantee a prosperous economy. They said a White servant cost three times what he could produce and that Savannah was languishing in contrast to Augusta, founded in 1736 and prospering with the help of eighty slaves imported from Carolina.

By 1740, settlers were leaving Georgia in large numbers for Charleston. There they published an eighty-page book of complaints and accusations against Georgia Trustees. The main complaint concerned “denying the use of negroes and persisting in such denial after, by repeated applications, we have humbly demonstrated the impossibility of making improvements to any advantage with White servants.”

Thomas Stephens, leader of the attack on the antislavery ban, came from England in 1737 to join his father and to assist in supervising his father’s Georgia holdings. By 1739, he had concluded that a slave would bring in ,75 more profit than a hired White worker. The next year, he said that a landowner using White labor would always be much poorer than one who used Black slaves. Stephens returned to England to promote the introduction of slavery against the desires of Oglethorpe and the Trustees. He returned to Georgia in 1741 and, with the support of the colonists opposed to Oglethorpe’s ban on slavery, published a tract in London the following year that forced Parliament to debate the subject. By then, some of the Trustees were moving to support the introduction of slavery. Other Trustees and Oglethorpe continued to oppose slavery on the grounds that it would endanger the colony, cause deaths, and necessitate unproductive guard duty for Whites, who would be better engaged in producing commodities for the corporation.

The Trustees’ position was reinforced by petitions supporting their ban on slavery from the Scotch Highlanders and the Germans from Salzburg, Austria, who had settled in Georgia. One small group of Salzburgers came to Georgia in 1734 by way of South Carolina where they saw slavery in action and did not like it. (However, twelve slaves from Carolina helped them build their town of Ebenezer northwest of Savannah.) They engaged in silk production and logging and did not need slaves to prosper. When the Scotch Highlanders arrived in Savannah in February 1736, Oglethorpe settled them at Darien. This group numbered about 150 by 1739, when they and the Salzburgers petitioned for the maintenance of the ban on slavery.

In 1739, Oglethorpe had other matters to tend. The War of Jenkins’ Ear broke out that year — so named because the Spanish cut off the ear of the unfortunate English Captain Robert Jenkins, who then carried it about with him to fortify his crusade against the Spanish. This war merged into the War of the Austrian Succession and most of the fighting took place in Europe. Georgia was only a backwater in this global conflict, but Oglethorpe, a loyal Englishman, was interested in doing anything to weaken Spain, the Catholic enemy. He raised a small army, which included five hundred troops from South Carolina (it had not yet overcome the shock of the Stono rebellion), and invaded Florida. He marched toward St. Augustine, where, among the Spanish troops, there were two hundred Blacks, many of them runaways from Georgia. One of his goals was to wipe out Fort Mosa, built by the Spanish two miles north of St. Augustine to protect a colony of slaves who had run away from the Carolinas. This action, though unsuccessful, was consistent with one of the reasons for founding Georgia — insulating Carolina slaves from Spanish enticements.

The fighting in Georgia that most influenced the lifting of the ban against slavery was the Battle of Bloody Marsh, where Georgians beat off Spanish counterattacks on St. Simons Island in 1742. This repulse of the Spanish effectively ended the Spanish threat to Georgia and thus partly negated one of the reasons for banning slavery — that slaves in Georgia would be potential allies of the Spanish.

The pressures resisting the establishment of slavery were too weak to prevail. De facto slavery had existed from the colony’s inception, and well before the ban was lifted, slaves were sold openly in Savannah while magistrates refused to enforce the ban. The Salzburgers and the Highland Scots argued that Africans had natural rights, but these settlers were minorities far from the seat of power. The ban on slavery was lifted as of January 1, 1751, due to several factors: Immigration had slowed, many settlers had left for the Carolinas, Oglethorpe paid little attention to Georgia after 1742, and clerical support for the legalization of slavery had increased.

The proponents of Black slavery dusted off the old environmentalist doctrine that the Enlightenment had picked up from classical Greece and passed on to the New World. This held that climate determined a people’s nature, abilities, attitudes toward freedom, and even intelligence. The French political philosopher, Baron de Montesquieu, circulated the environmentalist notion that people would work in hot climates only if forced to do so; therefore, slavery was rational in such places. The Rev. Alexander Hewat of Savannah used the environmentalist theory to argue for the introduction of slavery.

More religious support for slavery came from George Whitefield, who brought religious revival to Georgia in 1738. Whitefield was the first “American” public figure to be well known in all the colonies. A disciple of John Wesley’s, Whitefield was a remarkably effective preacher who had greatly stimulated the Great Awakening, a revival movement that started in New England and swept through the colonies in the early eighteenth century.

When he came to Savannah in 1738 to found an orphanage, Trustees gave him five hundred acres for his project, which he named Bethesda. It was partly funded from the profits earned from slave labor on the eighteen hundred acres Whitefield owned in South Carolina. By 1742, he had joined those clamoring for more slavery in Georgia. Whitefield argued that God made Georgia for Black labor because He made the climate so hot. “If they should see good to grant the limited use of Negroes,” Whitefield said, “Georgia would be as flourishing a colony as South Carolina.”

Whitefield did more than anyone else in Georgia to ease the troubled minds of those who wondered if Christianity was incompatible with slavery. Christians often said they believed they had a duty to convert non-Christians. If slaves were converted, could they remain slaves, or did Christian brotherhood require their freedom? Many believed so, and this inhibited conversion of the slaves. Whitefield helped convince Georgians that Blacks could be good Christians and yet remain slaves. The brotherhood of man, he argued, did not apply on earth, but only in heaven. Although Whitefield criticized the brutal treatment of slaves, his recommendation to the Georgia Trustees to legitimize slavery carried great weight and influence.

In 1750, the Trustees petitioned the British government to rescind the 1735 ban and recommended that there be one White for every four slaves, religious instruction for the slaves, and as little Sunday work as possible. To ensure that skilled White workers would not have to compete with Blacks, they urged that Black labor be used in agriculture only, except that coopers and sawyers might have black apprentices. The end of the ban was recognition that slavery already existed in Georgia and that the profit-minded colonists would prevail despite Oglethorpe’s desires.

After the ban was lifted in 1751 and Georgia became a royal colony, the revision of land policies opened the door to large plantations, and the number of Black slaves increased dramatically. In 1750, the six hundred Blacks in Georgia comprised 16 percent of the total non-Indian population. By 1760, there were thirty-five hundred Blacks constituting 35 percent of this population. The 1763 victory of the British over the French in the Seven Years’ War further stimulated Georgia’s development. By 1773 there were fifteen thousand Blacks in Georgia constituting 45 percent of the colony’s population.

Throughout the New World, whenever opposition to slavery or pleas for better treatment of Native Americans and Africans conflicted with the quest for greater profits, the humanitarian impulse was overwhelmed. While the English tried for a few short years to avoid Black slavery in Georgia, their failure to do so guaranteed a growing dependence on slave labor. This dependence quickly grew so strong that maintaining slavery became more important to Georgia’s officials than victory over the British in the American Revolution.

Liked this post? Follow this blog to get more.