Above: Georgia Revolutionary War hero Austin Dabney

Chapter One, Part 2: The American Revolution in Georgia is excerpted from The Way It Was in the South: The Black Experience in Georgia, by Donald L. Grant. Available from University of Georgia Press.

Read Part 1: Beginnings of Evil, or An English Experiment Gone Awry

About the book

At the age of 52, my father received his PhD in History from the University of Missouri and accepted a position at Fort Valley State College (now University), a public HBCU in Middle Georgia south of Macon. Throughout his tenure and beyond, he worked on what turned into a monumental history of Black Georgians. Unfortunately, he died in 1988 without getting it published. After his death, I reviewed his work. Recognizing its value, I editing the massive 1,500-page manuscript down to publishable length and extended the narrative’s timeline into the 1990s. (That turned into a story in and of itself.) Fortunately, there was a good deal of interest in the book and it was originally published in hardcover in 1993. It received a good deal of critical acclaim and received Georgia’s nonfiction “Book of the Year” award in 1994. It was later published in paperback by the University of Georgia Press.

At the age of 52, my father received his PhD in History from the University of Missouri and accepted a position at Fort Valley State College (now University), a public HBCU in Middle Georgia south of Macon. Throughout his tenure and beyond, he worked on what turned into a monumental history of Black Georgians. Unfortunately, he died in 1988 without getting it published. After his death, I reviewed his work. Recognizing its value, I editing the massive 1,500-page manuscript down to publishable length and extended the narrative’s timeline into the 1990s. (That turned into a story in and of itself.) Fortunately, there was a good deal of interest in the book and it was originally published in hardcover in 1993. It received a good deal of critical acclaim and received Georgia’s nonfiction “Book of the Year” award in 1994. It was later published in paperback by the University of Georgia Press.

Chapter One

The Formation of Georgia

Part 2: The American Revolution in Georgia

Revolutionary fervor seized Georgia somewhat later than it did other colonies. In 1769, a mass meeting of Savannah merchants resolved to protest implementation of the Townshend Acts and curtail imports of British goods, emulating the boycotts initiated by other colonies. Georgians vowed to admit no American slaves after January 1, 1770, or import African slaves after June 1 that year. In May 1770, when South Carolina was boycotting Britain to protest the Townshend Acts, it refused to accept shipments of slaves from British merchants. The slaves were then brought to Georgia and sold just under Georgia’s self-imposed deadline.

A few years later and still lagging a bit, Georgia sent no delegates to the First Continental Congress in the fall of 1774. However, the following January, Georgians approved the resolutions of that Congress. Georgia was represented at the Second Continental Congress, which organized the war effort against the British and adopted the Declaration of Independence.

Thomas Jefferson’s original draft of the declaration contained a section condemning the slave trade and castigating King George III for his resolve “to keep open a market where MEN should be bought and sold” and then inciting the same slaves to rebel and murder their masters. Jefferson’s position was too radical for South Carolina and Georgia delegates. They refused to sign any declaration that criticized slavery or the slave trade lest it encourage slave rebellions and strengthen the movement for abolition. The offending paragraph was removed from the final draft. Georgians wanted to preserve slavery for the same reason they established it: It was profitable. “We cannot do without slave labor,” explained one Georgian. “Our whole economy would be ruined.”

The American Revolution proved that slaves were willing to fight and die for freedom and did not much care for whom they fought. Personal freedom was their goal, not political independence from Britain. If the Americans offered freedom in exchange for military service, fine; if the British offered it when the Rebels did not, as was the case in Georgia, then some slaves joined them.

The British and their German mercenaries, the Hessians, were well aware of American Black soldiers. One Hessian officer wrote in his journal, “No regiment may be seen in which there are not Negroes in abundance and among them are able-bodied, strong and brave fellows.” This was not the only Hessian experience with Black soldiers. The Hessian State Archives at Marburg, Germany, contain records of 6 Black Georgians among the 115 Blacks who served King George III during the Revolution as drummers, musketeers, military police, fifers, and wagon hands. The Hessian commanders were apparently pleased by their performance, and they continued to welcome Blacks into their forces throughout the Revolution.

Blacks also helped the revolutionary cause, but the Patriot leaders’ attitude toward Black soldiers was ambivalent. Shortly after the Battle of Bunker Hill, George Washington took command of the revolutionary forces. On July 9, he signed an order prohibiting Blacks, either free or slave, from enlisting in the Continental army. In September 1775, Georgia’s delegates to the Continental Congress supported an abortive move to discharge all Blacks already in the army. In response the November 7 proclamation by the British governor of Virginia, Lord Dunmore, to free slaves who fought for the British, Washington recommended the reenlistment of Blacks who had already seen service. By war’s end, slaves and free Blacks were sought after and welcomed into military units in all the colonies except Georgia and South Carolina. Georgia’s leaders consistently placed the preservation of slavery above victory over the British and refused to enlist Blacks into the Patriot cause as soldiers.

The war also offered many opportunities to run away from slavery. Estimates on the number of runaways vary from a low of 50 percent of the fifteen thousand slaves that were in Georgia at the outbreak of hostilities to a high of 83 percent. Historian John Hope Franklin estimated that Georgia lost three-quarters of her slaves. Of the thousands who escaped (at least temporarily) during the American Revolution, many escaped to the frontiers in western Georgia and south to Florida, where they often found refuge among the Indians.

There was widespread fear in Georgia that the British might declare an end to slavery. Georgia’s delegation to the Second Continental Congress believed that if a British force of one thousand were to land in Georgia and unfurl the banner of freedom for slaves, they would be joined by at least twenty thousand Blacks within two weeks. American Tory leader Joseph Galloway thought the British could enlist three times as many Blacks as Whites in an army to suppress the Americans. Maj. Gen. Robert Howe was also concerned about this when he wrote John Hancock early in 1777 that he would need seven or eight thousand troops to prevent the British from coming from Florida to Georgia and inducing slaves to revolt. Howe’s request was impossible to fulfill, for Washington had only thirty-six hundred soldiers in the Continental army then.

British field officers in the South informed London that abolishing slavery would end the rebellion. The idea of abolition was seriously debated in England, but there were too many Tory planters in the South who felt that a victory that deprived them of their slaves would strongly resemble a defeat. Another reason the British never raised the standard of general abolition was that their stake in the British West Indian plantation-slave economy was too great. The 750,000 Black slaves who labored there to enrich the British outnumbered the total in the thirteen colonies. The British feared that to arm and free all slaves in the Rebel colonies could lead to a chain reaction in the other colonies that might bring independent Black governments into power in the Caribbean. This happened in French Haiti fifteen years later.

Early in 1776, British officers on the Georgia coast promised freedom to defecting slaves of Rebels who would fight against their former masters and encouraged them to board ships at Tybee Island. Soon many did. Several fearful Georgia planters took their slaves to other places to prevent defections to the British. George Haverick, for example, removed sixty of his slaves to Virginia for safekeeping. Knowledge of the British offer became widespread among slaves. Whites had long been amazed at the speed and efficiency of the slaves’ underground “grapevine.” A Georgia delegate to the Second Continental Congress commented that “the Negroes have a wonderful art of communicating intelligence among themselves; it will run several hundred miles in a week.”

Nowhere were the results of Georgians’ refusal to enlist Blacks more obvious than in the events in and around Savannah. The city was protected by Continental troops and the Georgia militia from the outbreak of the war until its capture by the British on December 29, 1778. Blacks played a large role in this reversal of American fortunes.

General Howe, commander of Georgia’s defense of Savannah, was expecting a frontal attack, which would give his sharpshooters an opportunity to slaughter the British. However, the British, who had landed unopposed a short distance from the city, had an offer from a slave, Quamino Dolly, to guide them up a secret path and take the Americans by surprise. The British kept their main force in front, where they were expected by Howe, but out of range of the guns of Savannah. The completely distracted Howe was surprised by a flank attack of the British Highlanders guided by Dolly. When the Highlanders fell on Howe’s flank, the main British force began a frontal assault that completely routed Georgia’s thousand-man force. Dolly was only one of several Blacks who assisted the British as spies, guides, and couriers in this action. Had the Georgians held their position for only a few more days, reinforcements from Charleston might have prevented Savannah’s fall.

From their victory at Savannah, the British pushed north up the Savannah River and captured Fort Cornwallis and Augusta on January 29, 1779. One-third of the British forces occupying Fort Cornwallis were runaway slaves who played a vital role in defending against Georgian counterattacks at Briar Creek in March. Georgia lost over 350 men in this battle, while the British lost only 20 soldiers. In 1781, when Georgians recaptured Augusta, Thomas Brown, a British officer, escaped to Savannah with a contingent of two hundred Black troops that became the nucleus of the famous King of England’s Soldiers.

After the British captured Savannah, they continued to use Blacks to hold their prize. Sir James Wright, the reinstalled Tory governor, had the legislature approve the impressment of four hundred Blacks to construct fortifications and the arming of Blacks in a crisis. Historian Benjamin Quarles estimated that from one thousand to four thousand Blacks, mostly slaves who fled from Rebel masters, assisted in fortifying Savannah. That fall, when Georgians besieged Savannah in a vain effort to retake it, several hundred Blacks, armed by the British, played an active role in skirmishes. When Savannah was finally surrendered to the Americans, Black troops made up 10 percent of the total British force.

The British continued to follow the policy of freeing Rebels’ slaves when they sought refuge with the British. However, the slaves of loyalists remained chattel, and if their masters wanted to take them to the British West Indies, they remained in bondage there. Patriot Georgians also used slave power to help with the Revolution, mainly as labor for the military. As early as November 4, 1775, the Georgia Council of Safety ordered a hundred slaves impressed to help Gen. Charles Lee prepare Savannah’s defenses against the anticipated British attack. Two years later, in a more general impressment act, masters were ordered to submit lists of male slaves aged sixteen to sixty-one. One-tenth of them could then be impressed, with the master receiving three shillings per slave for the twenty-one-day term of service. Although fines might be levied against masters who failed to furnish the lists, the act was difficult to enforce, and compliance was poor. In June 1776, the Council of Safety authorized the hiring of slaves to build entrenchments around Sunbury and had Col. Andrew Williamson hire Negroes from their masters to repair the road between the Ogeechee and Altamaha rivers. He was empowered to impress slaves for ten-day periods but had to use them in their home districts. This action was unpopular among slave owners, whose private interests outweighed patriotic sentiments.

Overall, more Blacks served the Patriot cause than the British, but this was not the case in Georgia. The main reason Blacks in Georgia served the king rather than the cause of the Revolution was that the British freed Rebel-owned slaves who defected to their ranks and were willing to fight. While the Continental Congress declared all White indentured servants free and the states made provisions to pay their masters for the time remaining in the indentures, not only would American forces in Georgia return captured slaves to their American masters, but they consistently refused to free the slaves of Tories, although the New England states did so. Tory-owned slaves were usually spoils of war in Georgia. Sometimes they were even returned to their Tory masters by Rebels — for a fee.

The slaves Patriot Georgians captured from the enemy were used in various ways. Some worked in lead and salt mines, and some were forced to build military fortifications, as, for example, the twenty axmen taken from the British and forced to construct batteries at Tybee Island. In June 1778, the General Assembly authorized the use of two hundred confiscated Tory-owned slaves for labor service in a Continental army expedition against East Florida; hundreds of others labored for the Georgia militia.

The Georgia Executive Council in 1780 ordered the slaves captured at Savannah to be sold and the proceeds divided among the soldiers taking part in the action. On one occasion, Georgia donated a slave to every soldier taking part in one campaign. Georgia also used captured slaves as money to buy provisions and pay soldiers. In 1782, Governor John Martin received ten slaves in lieu of his salary, and one month earlier, the entire Executive Council took its pay in slaves. Altogether, more Tory slaves were seized by the Rebels in Georgia than in any other state. The Tory plantations in the coastal region, including those of Governor Wright, who owned 523 slaves on eleven plantations, were especially vulnerable to Rebel raiders. The final stages of the Revolution in the South were largely financed by the sale of slaves confiscated from the Tories.

The best clear chance for Georgia to use Black soldiers to shorten the war and ensure victory came in March 1779, when Congress agreed to pay masters up to $1,000 for each slave under thirty-six years of age who passed muster. The Blacks would remain slaves while fighting in the Continental army, and upon discharge they would receive their freedom and a fifty-dollar bonus. That year, Congress sent John Laurens, one of Washington’s staff officers and son of the Continental Congress’s president, Henry Laurens, to Georgia and South Carolina to raise three thousand slave soldiers for the Revolution. This and later attempts in 1782 ended in failure. Both colonies held that arming slaves was too high a price to pay for victory.

Rather than weaken slavery in Georgia, the planter class preferred to weaken the struggle for independence.

Georgia not only refused to let her slave power be used to win the war; ever fearful, she passed a law in 1778 requiring that one-third of the state’s troops remain in their home counties to provide manpower to guard against insurrections and for slave patrols to prevent runaways. After the war was over, Georgia did come around to using free Blacks in the military as a labor force, as pioneers, and as musicians in the state militia. But they were not used extensively and were not armed. Decades before the Revolution, Blacks, both slave and free, had been used occasionally in Georgia’s colonial militia, but Georgia never had more than a few free Negroes in the militia, and it had never armed slaves. Provisions made in 1755 for accepting slaves in the Georgia militia included granting freedom for acts of valor. An unimplemented 1772 legislative act provided for arming slaves in an emergency and for awarding freedom for outstanding examples of heroism by slave soldiers.

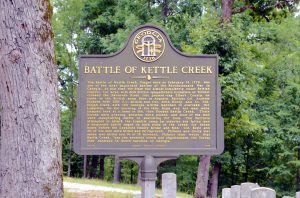

Not all Georgians opposed the use of Blacks in the revolutionary cause. The general policy of the time permitted one to send a substitute in his place when called to service. Many Northern slaves went as their master’s substitute and exchanged their uniforms for freedom when the conflict was over or when their terms of service expired. This happened occasionally in Georgia. The most famous surrogate was Austin Dabney, born a slave and brought into Georgia from South Carolina by his owner, who freed him to enlist as his substitute. Georgia permitted this occasionally for free Blacks but not for slaves. Dabney served the state militia well and was in several engagements, including the crucial Battle of Kettle Creek in North Georgia on February 14, 1779. One of the bloodier battles fought in Georgia, Kettle Creek was a great victory for the Americans, who surprised and defeated a force of seven hundred Tories, ending a long string of Rebel defeats that started with the fall of Savannah.

Not all Georgians opposed the use of Blacks in the revolutionary cause. The general policy of the time permitted one to send a substitute in his place when called to service. Many Northern slaves went as their master’s substitute and exchanged their uniforms for freedom when the conflict was over or when their terms of service expired. This happened occasionally in Georgia. The most famous surrogate was Austin Dabney, born a slave and brought into Georgia from South Carolina by his owner, who freed him to enlist as his substitute. Georgia permitted this occasionally for free Blacks but not for slaves. Dabney served the state militia well and was in several engagements, including the crucial Battle of Kettle Creek in North Georgia on February 14, 1779. One of the bloodier battles fought in Georgia, Kettle Creek was a great victory for the Americans, who surprised and defeated a force of seven hundred Tories, ending a long string of Rebel defeats that started with the fall of Savannah.

Dabney was badly wounded in the fighting. He suffered a broken thigh and was mustered out a free but crippled man. He was befriended by a White man, Giles Harris, whose family nursed Dabney back to health. In the early 1800s, Dabney moved to Madison County and became a racehorse fan. When Georgia gave land to revolutionary war veterans in the 1819 land lottery, Dabney was excluded because he was Black. However, a special act of the legislature in 1821 awarded him 112 acres in Walton County. He also received the same federal pension that White veterans received.

The names and deeds of Blacks were often left out of Colonial and revolutionary war records — which also are incomplete for Whites. However, records show that two other Black Georgians won their freedom by fighting for the Americans: David Monday, a slave whose owner was paid 100 guineas by the state in order to emancipate him, and Joseph Scipio, a private in the Fourth Regiment. Others will be forever anonymous.

One interesting example of the use of Blacks on the American side occurred when an effort was made to recapture Savannah from the British in 1779. France had entered the war on behalf of the colonies in 1778, and on September 23 the following year, the French fleet, commanded by Adm. Charles Henry d’Estaing, joined fourteen hundred American troops under Gen. Benjamin Lincoln to besiege the three thousand-man British garrison in Savannah where Tory general Augustine Prevost had five hundred Blacks in his force. The French brought four thousand soldiers with them, including the Black 545-man volunteer Chasseurs Brigade from Haiti. Although this combined operation did not succeed in recapturing Savannah, it was the prime example during the Revolution of Blacks fighting on both sides in the same battle.

Blacks worked on strengthening fortifications and collected naval stores throughout the British occupation. When the British were forced to evacuate Savannah in July 1782, at the end of the war, they took the Blacks, who were in two fundamentally different categories: the slaves of Tories and those who ran away from Rebel masters to join the British. Most of the Tory slaves were taken by their masters to the British West Indies or to Florida, which Britain wrested from Spain as part of the fruits of her victory in the Seven Years’ War, concluded by the Treaty of Paris in 1763. British planters who fled to Florida believed the area would remain British. This hope was shattered the following year when England returned Florida to Spain as part of the overall settlement of 1783 that ended the American Revolution.

In 1783 there were seven thousand Black slaves and one thousand free Negroes in Florida. Many of the slaves were taken by their owners back to Georgia when Florida was returned to the Spanish. There they were either kept by ex-Tories who made their peace with the new nation and settled down as planters or were sold to planters who had been Rebels during the war. In some cases where identification could be made, slaves who had defected to the British were reclaimed by their masters.

What happened to the slaves of the Rebels who fled to the British in response to the British promises of freedom? Although the Rebels tried to stop this flow of runaways by telling slaves that the British would only sell them into slavery in the West Indies, this did not happen to most of them. The Georgia legislature sent emissaries to buy escaped slaves back from the British prior to evacuation, but the British refused to sell them. Individual Georgians also tried to buy back slaves who had taken refuge with the British, who insisted the Blacks who voluntarily joined them were free.

The British evacuated 1,568 Blacks from Savannah to Jamaica in six ships. Later, about two thousand were taken to St. Augustine. Altogether, some four thousand Blacks were evacuated from Savannah. Just after the evacuation, the price of slaves in Georgia more than doubled, but the shortage was so great, they were hard to obtain at any price. Rice production suffered for years due to the labor shortage.

Although a few free Blacks stayed in Florida or the British West Indies, the British eventually took most of them to Canada, where they were given land and an opportunity to start new lives as free men. However, life there was a disappointment. While better than slavery in Georgia, it had drawbacks. The climate was severe, the land they were allotted was not the best, and there was prejudice and discrimination against them by the White British Canadians. Some were sent back to Africa and established communities in Sierra Leone.

One of the major diplomatic problems of the new nation was that of prevailing upon Britain to return the Blacks who had deserted the Rebels and sought refuge with the British during the Revolution. The controversy raged for decades. The Continental Congress considered the question before the British actually started their evacuation. Georgia’s delegates led the fight in 1782, and they were joined by all the states except New Hampshire, New Jersey, and Maryland to pressure the British to return the refugees. In 1783, George Washington was instructed to get the runaways back, and Congress resolved that the British were not to remove the Blacks. James Madison’s notes on the congressional debate on May 8, 1783, indicate that delegates were interested in a proposition according to which the United States would not release any British prisoners until the runaways were returned. All U. S. diplomats were instructed to make the return of these Blacks a high priority in negotiations. As early as May 26, 1783, U. S. ministers in Europe protested the failure of Britain to return these Blacks, whom the United States considered still slaves. Britain was denounced as a “slave stealer” time and time again.

Another way Blacks tried to obtain freedom and independence was to escape to the wilderness and establish communities there. Formation of these enclaves, or maroons (from the Spanish, “Cimarron,” meaning wild and unruly) had been a long-established method of resisting slavery. Slaves would desert their masters and go off and eke out a subsistence from the game and food plants of the area, sometimes supplementing this with booty taken by raids on settlements. Maroons existed in Georgia even before the American Revolution. In 1771, Georgia’s acting governor, James Habersham, who had earlier been the most active importer of slaves to Georgia, sent militiamen and Indian warriors to wipe out several slave maroons between Savannah and Ebenezer. He said they were marauders, preying on the countryside, and he feared the number of maroons would multiply if not promptly destroyed. The militia had to be called out the following year for the same purpose.

Of the free Negroes with the British at the time of the evacuation, there was one group that chose not to leave Georgia, a group of three hundred runaway slaves who had answered the British call to fight for their freedom. Some had joined the British at Savannah; others, at Augusta. When that city fell, they succeeded in making their way back to safety in Savannah, calling themselves the King of England’s Soldiers. They elected to try to make an independent life for themselves by building armed camps on the river between Savannah and Augusta instead of leaving with the British. This band was described as the “best disciplined band of marauders that ever infested (Georgia’s) borders.” Finally, on May 6, 1786, militia from Georgia and South Carolina, guided by Catawba Indians, surprised the fortified maroon and destroyed it. Many of the Blacks fought to the death; others were captured, and some escaped.

# # #

The great irony of the American Revolution is that it was not revolutionary enough. In 1775, Thomas Paine’s newspaper article “African Slavery in America,” called for ending the slave trade, abolishing slavery, and providing land for Blacks so that they might have true independence and the economic opportunity necessary for the pursuit of happiness. However, there were few, if any, gains from the Revolution for most Blacks in the United States. Black initiatives, the need for soldiers, plus the rhetoric of freedom and liberty did encourage the weakening of slavery in the North, and most of the five thousand Blacks who fought on the American side, if they were not already free when they enlisted, received freedom as their reward for patriotic duty. Also, the view of the slave trade as an unmitigated evil grew during the Revolution.

In Georgia, the worst was yet to come. The war for liberty was followed by an increase in slavery and a reduction in the liberties of Blacks. A few Blacks were freed as a result of the Revolution and were permitted to remain in the state, but the institution of slavery was not weakened, nor was the status of Blacks improved. On the contrary, an ever-tightening and constricting net was thrown over the Blacks of Georgia during the next eighty years. By the outbreak of the Civil War, Blacks had fewer freedoms than they had before and during the Revolution.

During the war, as slavery was undermined in the North, it was made more binding in the South, and the seeds of later sectional conflict were sown. The Revolution’s failure to develop a commitment to freedom for Blacks has led many historians to conclude that the Civil War was a consequence of the American Revolution. Perhaps Jefferson regretted not taking a stronger stand in his final draft of the Declaration of Independence, for later, when referring to the slavery issue’s divisiveness, he said, “I tremble for my country because I know that God is just.”

Liked this post? Follow this blog to get more.