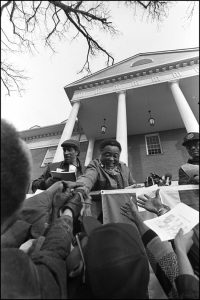

Above: Some of the 25,000 who came for the second march on Jan. 24, 1987

Excerpt from The Way It Was in the South: The Black Experience in Georgia, by Donald L. Grant and Jonathan Grant. All rights reserved.

Excerpt from The Way It Was in the South: The Black Experience in Georgia, by Donald L. Grant and Jonathan Grant. All rights reserved.

The most startling event during the 1987 King holiday celebration grew out of a “march for brotherhood” at the Forsyth County seat of Cumming on January 17, when a small group of marchers led by Hosea Williams was attacked. Forsyth, just north of Fulton County, was home to thirty-eight thousand people, all of them white. It had a reputation as a racist enclave ever since whites had driven out virtually all the county’s eleven hundred blacks in 1912 after a lynching and orgy of nightriding and whitecapping.

Blacks were made to feel unwelcome whenever they set foot in Forsyth. Signs posted in the 1960s warned: “Nigger — Don’t Let the Sun Set on You in Forsyth County.” The signs meant business. After Lake Lanier was created on the east boundary of Forsyth County, it became a popular recreational area and a destination for white flight from Atlanta. Some Atlantans who built cabins there found notes on their doors saying, “Don’t bring your maid the next visit.” In 1968, ten black boys and their counselors on a camping trip from Atlanta to Lake Lanier were told to leave Forsyth County or be carried out “feet first.” In 1976 a cross was burned when one black rented a slip for his boat at the Bald Ridge Marina. Black truck drivers making deliveries to the Tyson chicken-dressing plant in Cumming had to be escorted by Georgia Bureau of Investigation (GBI) agents as late as the 1970s. In 1980 a black Atlanta firefighter was shot and wounded while driving near Lake Lanier. Two years later, another black was shot in a racial incident at the lake; a black couple also was shot and wounded. J. B. Stoner’s Thunderbolt blamed removal of the warnings for such incidents.

Charles Blackburn, a white karate teacher in Cumming, had the original idea for the 1987 march, but he got so many threats he canceled his plans. Then Dean and Tammy Carter of nearby Gainesville took up plans for the march. They were joined by the crusty Williams, who was ready to march once more. On Saturday, January 17, they led seventy-five marchers, mostly from Atlanta, to Forsyth County in a “Brotherhood Anti-intimidation March.” They arrived late, and the seventy-five-man police and state-trooper force assigned to protect them was unable to stop a crowd of about five hundred Klansmen and sympathizers from overwhelming the police lines.

The counter-demonstrators had been worked up to a fever pitch by hate speeches by J. B. Stoner, who had been released from his Alabama prison sentence for church bombing just two months before. Grand Dragon Dave Holland of the Southern White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan joined Stoner in whipping members of the crowd, waving Confederate battle flags, into a frenzy. Hundreds of jeering, screaming whites broke through the police cordon and threw rocks and bottles at the marchers while shouting racial slurs. Williams said, “In thirty years in the civil rights movement, I haven’t seen racism any more sick than here today.” The march was called off when police told the marchers that they could not ensure their safety. Officers arrested eight of the most violent Klansmen. All but one were Forsyth County residents.

News of the attack spread quickly. Pictures of hate-contorted faces and flying rocks and bottles were reminiscent of the brutality of Birmingham and Selma in decades past. On Sunday, the Klan attack was discussed throughout the nation; it had come amid concerns about the increasing number of racial incidents in the United States.

In marking the King holiday on Monday, Coretta King spoke from the site of her husband’s tomb and said, “Match bigotry with courage and resist violent acts with nonviolence.” Williams and Dean Carter held a joint news conference that evening to announce another march in Forsyth County the following Saturday.

The subsequent march drew national and international attention. More than twenty thousand marchers went to Cumming, some chanting “Forsyth County, have you heard — this is not Johannesburg.” About two thousand counterdemonstrators showed up with Confederate flags and hateful banners: “The Great White Hope — Sickle Cell Anemia” and “James Earl Ray — Great American Hero.” Fifty-five of the counterdemonstrators were arrested, mainly on assault charges. Over seventeen hundred National Guardsmen and five hundred other lawmen were there to control the white supremacists. The march concluded with speeches. One by Williams listed six demands that included the formation of a biracial council in Forsyth, fair employment, and the return of property lost by those forced to flee in 1912.

Forsyth’s community leaders were upset, because racial violence was bad for business. After the January 17 Klan riot in Forsyth County, the Mead Corporation canceled any plans it may have had for a five-thousand-worker plant there. The Chamber of Commerce moved to deemphasize the importance of the attack on the marchers and, in the interests of continued economic development, took out full-page newspaper advertisements declaring that the racists did not represent Forsyth County.

The subsequent march drew national and international attention. More than twenty thousand marchers went to Cumming, some chanting “Forsyth County, have you heard — this is not Johannesburg.” The march was a major media event. There was almost a traffic jam of helicopters. About two thousand counterdemonstrators showed up with Confederate flags and hateful banners: “The Great White Hope — Sickle Cell Anemia” and “James Earl Ray — Great American Hero.”

Fifty-five of the counter-demonstrators were arrested, mainly on assault charges. Over seventeen hundred National Guardsmen and five hundred other lawmen were there to control the white supremacists. The march concluded with speeches. One by Williams listed six demands that included the formation of a biracial council in Forsyth, fair employment, and the return of property lost by those forced to flee in 1912.

The march was a major media event. There was almost a traffic jam of traffic overhead as police and media choppers jockeyed for position. In addition, several foreign correspondents covered the event. The largest civil rights demonstration in Georgia history was unique because white participants outnumbered blacks, and those arrested were trying to thwart racial progress, as opposed to the old days, when those seeking to promote it spent time in jail. In 1987, both of Georgia’s U. S. senators joined a hundred local church and civic leaders to greet the marchers and wish them well.

The class-action suit filed by Williams and other marchers in March 1987 against the Forsyth County assailants for their activities during the January 17 march went to trial in 1988. A federal jury in Atlanta levied $950,000 in damages against Daniel Carver, Holland, Ed Stephens of Jonesboro, eight other individuals, the Southern White Knights, and the Invisible Empire. Williams announced that he wanted to be dropped from the suit because he did not want “to take away from them their hard-earned possessions simply because they brutalized us in responding to the sicknesses of our capitalistic society.” The U. S. Supreme Court upheld the award, and the plaintiffs were partially successful in collecting damages.

Events in Forsyth County indicated how much Georgia had developed since World War II. The brutality that symbolized an earlier era was neither encouraged nor tolerated. Blacks could go most places that whites could, and expressions of belief in racial equality were common. Even the Klan said it was not antiblack; it simply wanted “white rights.” There were subsequent marches, both by Williams and the Klan. In other ways, little had changed. In 1990, black workers were employed in Forsyth County, but no African-Americans were reported living there.

Suggested reading

Nonfiction: Blood at the Root by Patrick Phillips. Link

Fiction: Brambleman by Jonathan Grant. Link

Liked this post? Follow this blog to get more.