Above: Sherman’s March to the Sea (Savannah Campaign), 1864

This post is excerpted from The Way It Was in the South: The Black Expericience in Georgia by Donald L. Grant and Jonathan Grant (University of Georgia Press, 2001). All rights reserved.

This post is excerpted from The Way It Was in the South: The Black Expericience in Georgia by Donald L. Grant and Jonathan Grant (University of Georgia Press, 2001). All rights reserved.

Publishing to critical acclaim, The Way It Was in the South: The Black Experience in Georgia was an American Heritage Editors’ Choice selection and also won Georgia’s “Author of the Year” honors for Dr. Grant.

About the Author: Donald Grant (1919?88) received his Ph.D. degree from the University of Missouri and was professor of history at Fort Valley State College (now University) in Middle Georgia. He was also the author of The Anti?Lynching Movement: 1883-1932.

And how this book came to be published after my father’s death is a story in an of itself.

Prelude to Conflict

By the time Georgia legalized slavery in 1750, the decision regarding black servitude seemed settled for all time. It required another 115 years of increasing tension and a great war to reverse this decision. There were many steps on the road to armed conflict. However, the fundamental reason for the Civil War was the South’s intransigence on slavery. The South’s unwillingness to alter its “peculiar institution” and enter the modern world made a major convulsion unavoidable. Southern fears of the power of the federal government to interfere with slavery increased to the climax of 1860-61, when, one by one, states entered into open rebellion against the Union.

When Abraham Lincoln opposed the expansion of slavery into western territories, he was, as far as the Southern oligarchy was concerned, pronouncing the death knell of slavery. With Georgia in the front ranks, the South marched off to war to preserve and extend slavery under a cloak of “states’ rights” rhetoric. Although the slave interests did not start hostilities against the Union until 1861, they had been prepared to leave it over the issue of slavery time and time again ever since the nation was founded. In 1830, the Milledgeville Federal Union said, “The moment any improper interference is attempted with our slaves, we say, let the Union be dissolved,” and the Macon Georgia Messenger said prophetically that only a bloody civil war could end slavery. Prompted by an antiabolitionist convention in Athens, the Georgia legislature in 1835 resolved that the preservation of the Union depended on the North crushing the abolition movement by denying abolitionists free speech and extending slavery into the territories.

The Compromise of 1850 was an effort to reconcile pro-slavery and antislavery interests that disputed over the disposition of Mexican War spoils. A five-point package was worked out in Congress that would admit California as a free state but not close the door to slavery in other western territories taken from Mexico. The compromise agreed to abolish the slave trade, but not slavery, in the District of Columbia. The provision that did the most to heighten tensions over slavery was the agreement to enact a new and far more severe fugitive slave law, one planters hoped would put an effective end to the underground railroad.

Georgia played a leading role in the Southern debate on the acceptability of the Compromise of 1850 when its leading citizens met in the capital at Milledgeville on December 13-14, 1850, and resolved, though reluctantly, to accept the compromise. In what became known as the Georgia Platform, the delegates warned the nation that the life of the Union was secondary to

their right to keep slaves and that Georgia would secede if slavery was abolished in the District of Columbia without the consent of the slave owners, if the domestic slave trade was limited in any way, or if Congress refused to admit new slave states or abolished slavery in the territories. They viewed the new Fugitive Slave Act as the crux of the matter and resolved: “That it is the deliberate opinion of this convention, that upon the faithful execution of the Fugitive Slave Bill by the proper authorities, depends the preservation of our much loved Union.” The poor enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 was a source of bitterness in Georgia. The Craft case especially reinforced Georgia planters’ doubts concerning its practicality.

In the territories, tensions continued to rise over the issue. Georgians watched events in “Bleeding Kansas” with interest, but they were horrified when they learned of militant abolitionist John Brown’s raid at Pottawatomie Creek on May 25, 1856. In 1857, the legal position of all blacks in the United States was greatly weakened by the Dred Scott Decision, which opened the way for the expansion of slavery into the western territories. The Supreme Court ruled that slaves had no rights and that the federal government had no authority to regulate slavery or to interfere in state regulation of slaves.

The single event that most shocked the slave society was Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia, on October 16, 1859. News that Brown had seized the federal arsenal and intended to arm slaves in a chain of counties extending through Georgia and other states to bring an end to slavery spread like wildfire throughout the South and caused panic in Georgia. In one typical reaction, Rome organized a hundred vigilantes to march to the aid of Virginia. Northern travelers, always under suspicion for kindling the fires of abolitionism among blacks, became even more suspect and were often forced to leave. Mob violence broke out in Savannah against a white accused of reading accounts of the raid to local blacks, and a mob seized a Yankee ship docked there. The Savannah Republican and the Columbus Sun both reported in November that a “squad of Brown’s emissaries” in Meriwether County were waiting to give battle. The burning of numerous cotton gins that same month was called “Kansas work in Georgia,” though such fires were common during the ginning season. Gov. Joseph E. Brown, who earlier had difficulties getting money appropriated for the state’s militia, had no problem getting $75,000 from the legislature after the news came from Harpers Ferry.

to arm slaves in a chain of counties extending through Georgia and other states to bring an end to slavery spread like wildfire throughout the South and caused panic in Georgia. In one typical reaction, Rome organized a hundred vigilantes to march to the aid of Virginia. Northern travelers, always under suspicion for kindling the fires of abolitionism among blacks, became even more suspect and were often forced to leave. Mob violence broke out in Savannah against a white accused of reading accounts of the raid to local blacks, and a mob seized a Yankee ship docked there. The Savannah Republican and the Columbus Sun both reported in November that a “squad of Brown’s emissaries” in Meriwether County were waiting to give battle. The burning of numerous cotton gins that same month was called “Kansas work in Georgia,” though such fires were common during the ginning season. Gov. Joseph E. Brown, who earlier had difficulties getting money appropriated for the state’s militia, had no problem getting $75,000 from the legislature after the news came from Harpers Ferry.

The single-minded abolitionist’s daring raid engendered a climate of hysteria that led to a flood of rumors regarding slave insurrections throughout the South. In the spring of 1860, mysterious fires broke out in Macon and six other Georgia towns. All were blamed on a slave conspiracy, with white abolitionists supposedly directing the operations. “Confessions” of insurrection were whipped out of blacks all over Georgia in late 1860. Rumors of slave revolts were especially rife in Northeast Georgia, though no part of the state was immune.

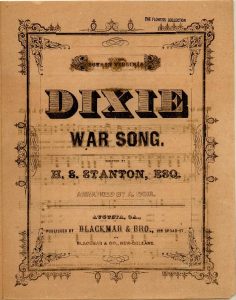

Fueling the already intense emotional climate was a new popular song. “Dixie” was first performed in 1859 and expressed Southern intransigence so well that it became for all practical purposes the Confederate anthem. H. S. Stanton of Georgia is credited with turning it into a war song. Among the many original verses of “Dixie” was:

Fueling the already intense emotional climate was a new popular song. “Dixie” was first performed in 1859 and expressed Southern intransigence so well that it became for all practical purposes the Confederate anthem. H. S. Stanton of Georgia is credited with turning it into a war song. Among the many original verses of “Dixie” was:

Hear the Northern thunders mutter!

Northern flags in South winds flutter!

Send them back your fierce defiance!

Stamp upon the accursed alliance!

Lincoln’s election in November 1860 increased the fears of slave revolt and led to a strengthening of the patrol system and tightened security over slaves. Mob violence against blacks and an occasional white considered sympathetic to abolition became a wave of terror. Frequent lynchings served to keep most slaves cowed, although the number of runaways increased. Trusted slave drivers had their hunting guns confiscated. Passes, especially for railroad travel, were severely restricted, and separate church services for blacks were curtailed. Some cities, like Macon, greatly enlarged their police forces in response to insurrection scares.

Georgia’s leaders had greeted Lincoln’s election with dismay. Lincoln, in his first inaugural address, promised to support a constitutional amendment that would guarantee slavery where it already existed. However, Lincoln would not agree to any extension of slavery. Southern planters were in basic agreement that slavery must expand or die. They believed that new lands had to be opened to slavery for three reasons: to replace lands worn out (by poor agricultural practices); to provide out-of-state markets for the continual increase in the slave population in order to prevent a class of idle blacks from appearing; and to enter new slave states into the Union at least as often as new free states so that slaveholding interests would not grow politically impotent in Congress. They foresaw a day, not too distant, when the ever-expanding and dynamic North would outvote them in Congress on every issue. This, the Southern oligarchy feared, would mean the demise of slavery.

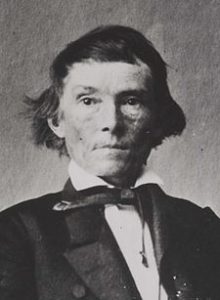

To Georgia leaders such as Howell Cobb and Robert Toombs, the election of Lincoln was the last straw. However, secession by the Southern states was neither unanimous nor simultaneous. The Georgia legislature debated the secession issue on November 13 and 14, 1860. Toombs led the firebrands, urging headlong action. He anticipated that lacking new markets to receive the surplus of 500,000 slaves he thought Georgia would produce through natural increase by 1900, the state would be impoverished. “We must expand or perish,” he declared, and demanded “resistance to Lincoln and his abolition horde.” Alexander Stephens headed those with a more moderate “wait-and-see” attitude and was labeled a “submissionist” and “crypto-abolitionist.” The legislature decided to refer the matter to a convention. Delegates to this convention were elected on January 2, 1861, when secessionists’ “propaganda skillfully exploited the voters’ racism, employing everything from vague rumors of slave insurrections to (Governor) Brown’s warning to nonslaveholders that submission to Lincoln would mean abolition, ethnic equality, and intermarriage,” according to historian F. N. Boney.

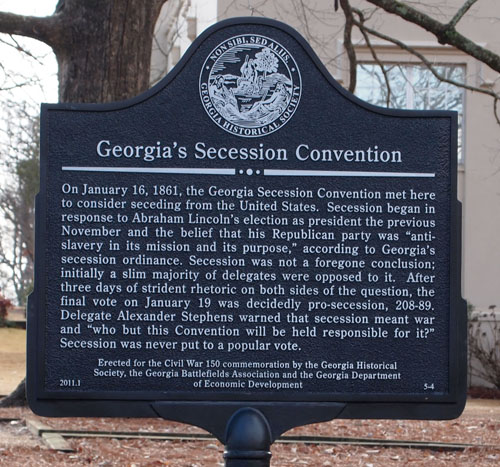

Delegates to the convention would decide if the state was to secede or not. Although Governor Brown stated that the popular vote for electing delegates was 50,243 for immediate secession and 37,123 for a more moderate course, later research indicated the margin “was paper thin, if it existed at all,” and the vote was no more than 44,152 for immediate secession to 41,632 against. Some evidence suggests a slight majority of voters favored cooperationist, not secessionist, candidates. “Georgians were so equally divided by the question of secession that the voters’ judgment can be justly termed a paralyzing indecision . . . when the delegates listened to the voice of the people and made the final decision to secede, their ears were more closely attuned to the shouts for secession than to the almost equally numerous whispers of doubt,” concluded historian Michael P. Johnson. Interestingly, Brown did not announce the vote totals until April, three months after the convention had done its business; official records of the vote do not exist.

Governor Brown, a thin, teetotaling Baptist lawyer from the hill country with a Yale law degree, called for the convention to meet at Milledgeville on January 16, citing as reasons the failure of the North to enforce the Fugitive Slave Law and the election of Lincoln, though he earlier had said Lincoln’s election by itself was insufficient reason for Georgia to secede. The move for secession was strongest in the plantation country, and convention delegates disproportionately represented slavery interests. Of the 301 delegates, 259 (86 percent) were slave owners; seven owned more than a hundred slaves, sixty-seven owned more than fifty, and almost half owned more than twenty slaves. In all, the delegates owned 7,660 slaves. Had the delegates been typical of Georgia’s white population, most would have owned no slaves at all. Proceedings were closed to outsiders, and the first convention vote on secession was only 166 in favor to 130 opposed. Terrific pressure was then put on the 130, and 41 were persuaded to switch their votes three days later.

Not only did planters want to maintain slavery, they also wanted to continue controlling yeomen and poor whites. Many who voted for secession did not foresee a war; Brown had said that secession before Lincoln’s inauguration would reduce the chance of war. Brown told

non-slave-owning poor whites that without secession the Union would buy and free the slaves and planters would use the money to buy their land and reduce them from landowners to tenants. Thirty percent of the delegates still voted to stay in the Union despite secessionist leaders’ propaganda, manipulation, and deception. On January 19, 1861, Georgia became the fifth state to pass an ordinance of secession, which was never offered to the people of Georgia for approval. The Augusta Chronicle and Sentinel, then the largest newspaper in the state, deplored the action. Georgia joined with other states to form the Confederate States of America on February 9, 1861, at Montgomery, Alabama. Georgia’s convention reconvened in March to adopt the Confederate Constitution (which also did not get popular approval) and to write the 1861 state constitution, which was approved by less than 52 percent of the voters in a very light turnout.

Secession resolved the tension and quelled the slave insurrection panic. The planter class again felt secure, in charge of its own destiny, and in the heady days of the secessionist enthusiasm, saw only a rosy future. As the Civil War proceeded, the rigor of the plantation system softened. Slaves remained a “troublesome property,” and lynching and burnings still occurred, but the paranoia diminished.

In Savannah in March 1861, Alexander Stephens, chosen to be vice president of the Confederacy, expressed the fundamental beliefs white Southerners had been busily teaching each other for generations. He said of slavery: “Its cornerstone rests upon the great truth that the Negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery — subordination to the superior race — is his natural and normal condition.” It was this racist bedrock, born of self-deception and assiduously cultivated since Georgia was founded, that obscured the relatively simple fact that slavery was an economic institution created to exploit the black worker. It was this racism that took Georgia out of the Union in 1861, that killed so many of its sons on the battlefields of the Civil War, impoverished its economy, and brought needless suffering to countless people, both black and white.

Coming soon: The rest of the story.

Liked this post? Follow this blog to get more.