By Jonathan Grant

@Brambleman

First of all, follow Eli!

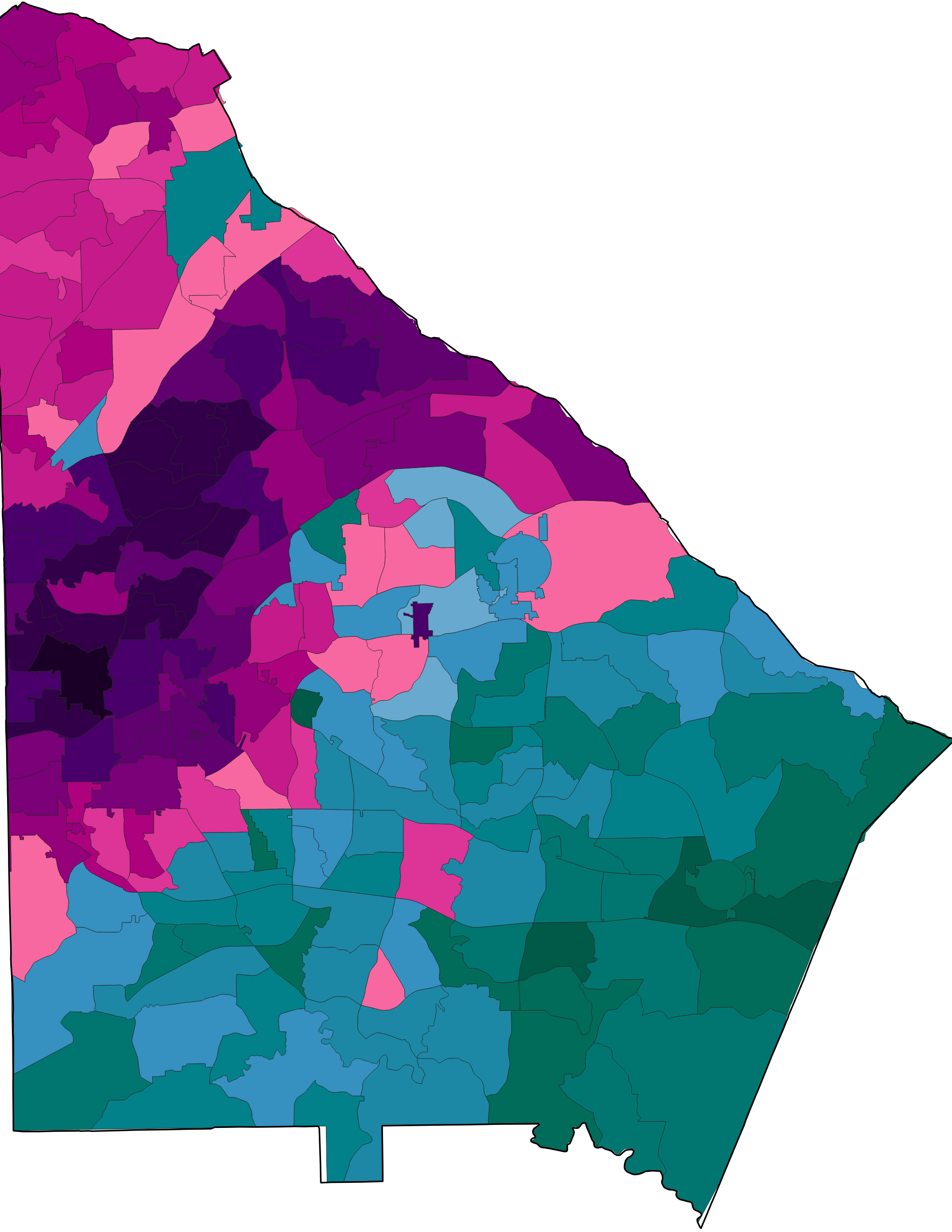

First of all, I want to thank Eli Spencer Heyman for digging through the data and drawing up these maps, as well as providing me with originals to use in this blog. A Georgia native, now a student at Brown, he does a lot of mapping, data compilation, and analysis. Lately, he’s been compiling a spreadsheet of Georgia’s municipal election results. His pinned tweet, as of today, is a geographic breakdown of Georgia’s momentous 1868 elections. So, if you’re on Twitter, and interested in politics–especially but not limited to Georgia–his twitter account is a must follow. So follow Eli!

A closer look at DeKalb’s referendum vote

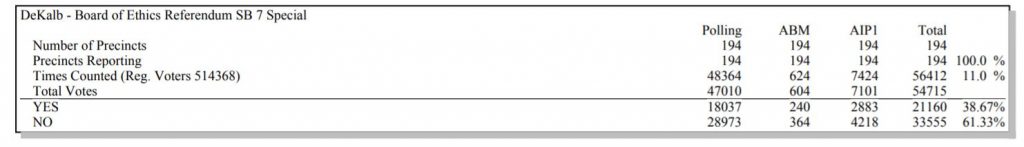

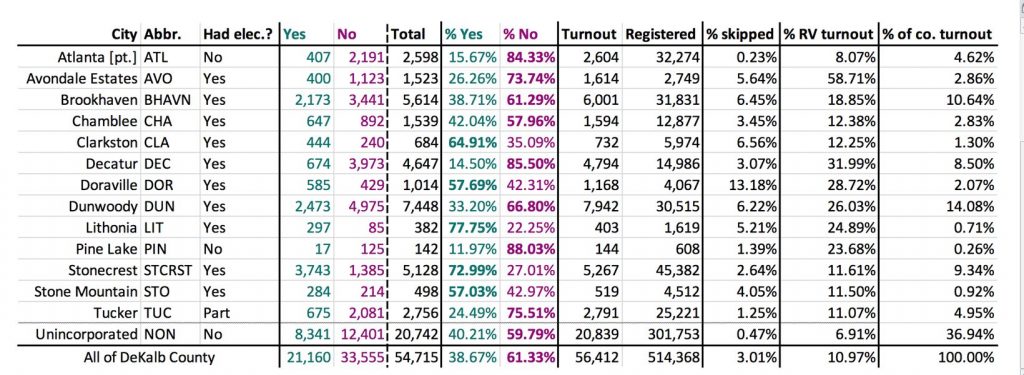

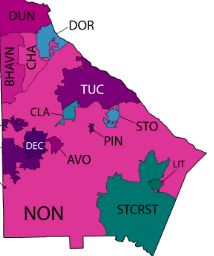

Just say NO: DeKalb strongly rejected Tuesday’s ethics referendum, with 61 percent voting against it in a low turnout election. Only 55,000 of 514,000 voters cast ballots, with most of them also participating in municipal elections. An analysis showed a close correlation between turnout and opposition: the higher a precinct’s turnout, the higher percentage of “No” votes. Much of the support for the referendum came in south DeKalb, the opposition in north and central sections of the county.

Just say NO: DeKalb strongly rejected Tuesday’s ethics referendum, with 61 percent voting against it in a low turnout election. Only 55,000 of 514,000 voters cast ballots, with most of them also participating in municipal elections. An analysis showed a close correlation between turnout and opposition: the higher a precinct’s turnout, the higher percentage of “No” votes. Much of the support for the referendum came in south DeKalb, the opposition in north and central sections of the county.

That being said, voters in the north DeKalb city of Doraville voted in favor of the referendum, and the heaviest opposition was in Pine Lake, south of Memorial Drive, where 88% percent voted NO. Even though the tiny town had no contested municipal elections, Pine Lake had a relatively high turnout: 28% compared to 11% countywide. Other strong rejections: Decatur (85%), Atlanta in DeKalb (84%), Tucker (75%), and Avondale Estates (74%). The strongest support came from Lithonia (78%) and Stonecrest (73%).

Eli breaks it down. Click to open in Twitter and feel free to retweet:

This Tuesday, DeKalb County held a referendum on reconstituting its ethics board (SB 7). It went down 61%-39%. The proposal was seen by most civil society groups as weakening the board; for example, whistleblowers would have had to go through county HR before going to the board. pic.twitter.com/DeQEbnYq1J

— Eli (@elium2) November 7, 2019

How did your legislator vote?

The results leave some legislators at odds with their constituents on the issue. In the House, SB passed 157-13; in the Senate, 53-1. Freshman Sally Harrell was the only senator voting against it. Here’s how DeKalb legislators voted on passage of SB7:

House

Voting Yes

Karla Drenner

Viola Davis

Bee Nguyen

Vernon Jones

Renitta Shannon

Billy Mitchell

Pam Stephenson

Doreen Carter

Dar’shun Kendrick

Karen Bennett

Voting No

Michael Wilensky

Scott Holcomb

Matthew Wilson

Becky Evans

Mary Margaret Oliver

Michelle Henson

Senate

Voting Yes

Emanuel Jones

Elena Parent

Steve Henson

Tonya Anderson

Gail Davenport

Gloria Butler

Voting No

Sally Harrell

Small Group, Big Voice

In unincorporated DeKalb, where the referendum was the only issue on the ballot, it lost 60-40, with only 21,000 voting (38% of the total county vote). The heaviest concentration of “No” votes outside municipalities came from a broad swath of precincts between Decatur and Tucker. This happens to be the home turf of referendum opposition leader Mary Hinkel.

Along with a handful of others, Hinkel set up the DeKalb Citizens Advisory Council. Its website was an essential source of information on the referendum. Hinkel and her comrades showed up at town halls and highlighted the referendum’s shortcomings, of which there were many.

Referendum opponents were gratified, even surprised at the measure’s lopsided defeat. “We didn’t know when we started what would happen,” Hinkel said after the election. “We took this on not expecting to win.” One of Hinkel’s co-organizers confided, “People told me we couldn’t win.”

“We just knew we needed to get the word out. So we knocked on doors and tried to educate people,” Hinkel said, adding that this election showed the value of citizen participation. “We need citizens to be engaged. It’s fundamental.”

For Hinkel, one big frustration was the referendum’s wording: “Shall the Act be approved which revises the Board of Ethics for DeKalb County?” This was the exact phrase that appeared on the ballot in 2015. But it wasn’t the same measure at all. At the Brookhaven town hall, DeKalb resident Paul Wolpe, head of Emory University’s Ethics Center, called the 2015 ethics bill, sponsored by Rep. Scott Holcomb, “close to model legislation for integrity and ethics in county government.” However, he strongly opposed the revisions to that code in SB7, adding, “I cannot find an actual justification for the revision.”

Nevertheless, the ballot wording gave this year’s referendum a built-in base of support. “People thought they were voting in favor of ethics,” Hinkel said, “so we were working against the language on the ballot, which was so vanilla.” She added a cautionary note: “It’s very important to be informed, and I think it shows that if you don’t know what’s on the ballot, you shouldn’t vote for it.”

About those shortcomings

Hinkel, who got more involved in local politics in response to city initiatives in North DeKalb, was alarmed at how Senate Bill 7, which set up the referendum, changed during the course of this year’s General Assembly session. At first, SB7 was a “clean fix” to bring the DeKalb Ethics Board’s appointment process in line with last year’s Georgia Supreme Court decision. The court ruled that private entities, such as the Chamber of Commerce or Leadership DeKalb, cannot appoint public officials. (By the way, this problem remains unresolved for agencies throughout Georgia.)

It ended up as sausage–something an ethically challenged politician’s attorney could be proud of. Some of the bill’s proponents have argued the changes were needed because DeKalb Ethics Officer Stacey Kalberman was “overreaching.” On the other hand, if any county needs tough love on ethics, it’s DeKalb. SB7’s features included replacing the Ethics Officer (an attorney) with an Ethics Administrator (a “paper pusher” in Hinkel’s words). Other changes–like forcing whistleblowers to go through the county’s Human Resources department, and allowing the County Commission to approve policies and procedures–would have weakened the Board’s authority and independence. You can read more here.

Back to the drawing board

For legislators, it’s back to the drawing board. Since the Supreme Court ruling forced the removal of four of seven Ethics Board members, the DeKalb panel doesn’t have a quorum and cannot conduct official business. Because it’s been hobbled this way for more than a year, there should be a sense of urgency on the issue.

Reps. Viola Davis and Matthew Wilson have already said they have plans to move forward on the issue. There is optimism that a bill can be passed and put on the ballot for the Presidential Primary on March 24, 2020. However, that seems like a very short time frame and could raise new concerns—and opposition—if legislators do anything other than simply fix the appointment process. Here’s hoping they avoid the downgrades this time.

Liked this post? Follow this blog to get more.