Above: Teresa Tomlinson, star of many Columbus Save-a-Pet PSAs, with rescue dog up for adoption

“The greatness of a nation and its moral progress can be judged by the way its animals are treated.” —

By Jonathan Grant

@Brambleman

While all seven Democratic candidates seeking to defeat Sen. David Perdue have platforms, more or less, Teresa Tomlinson is running on her record as two-term Mayor of Columbus, Georgia. (She also has more platform, for that matter.) “I’ve governed and I’ve governed well,” she tells would-be supporters and has receipts to back up the claim, including the St. Maurice Award she recently received for her support of Fort Benning and the Infantry.

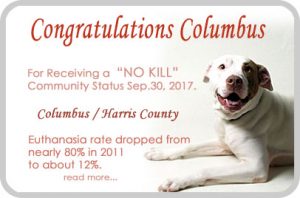

Passionate about policy, the Emory Law graduate talks about using government as a tool “to help people lead their most prosperous lives.” But not just people. Her Save-a-Pet program was remarkably successful and received a “Bright Ideas” award from Harvard’s Kennedy Business School. The Columbus animal shelter had an 80 percent euthanasia rate when she took office. In 2017, the year of the award, the city was declared a “no-kill community.” (This isn’t an absolute; typically it denotes a 90 percent save rate for animals.)

Teresa Tomlinson loves animals. She became involved in rescue efforts decades ago, when she lived in Decatur. After she moved to Columbus, she took it to the next level when a stray dog had six puppies in the crawl space of the home she shared with her husband, Wade (aka “Trip”).

After the puppies were retrieved from under the house, the Tomlinsons contacted the city’s animal shelter and learned there was no room for the dogs. Tomlinson ended up being a “foster mom” to the dogs, and she and Trip gave a substantial donation to fund construction of an emergency center.

Columbus voters would later approve a penny sales tax that funded a new, state-of-the-art facility on Milgren Road with heated floors and dog runs, but that didn’t solve the underlying problem. “For years, the high euthanasia rate and low live release rates had become a commonplace issue,” The Columbus Ledger-Enquirer reported. “In 2010, the euthanasia rate was as high as 79 percent and had become a public issue.”

“The drive to do better”

“I had worked mostly with Humane Society and PAWS,” Tomlinson said. “I didn’t know what was going on with the shelter.” That changed after she became mayor. “I’d just been sworn in and I got a call,” she said. “Somebody told me the shelter had an 80 percent kill rate. They’d completely run out of space.”

The city also had a five-day rule for claiming pets, with brutal consequences. “If you went on vacation and Fluffy got out, Fluffy was gone,” Tomlinson said. “It was horrific.”

The high euthanasia rate was not the result of malevolence, Tomlinson said. “These were good people. They didn’t hate animals. They love animals. It’s just there were all these antiquated policies bent toward animals being vermin and nuisances and disease-spreading.” The view that “any animal not in a home was a public health threat” was outdated, she said. “We had a wonderful facility we could do all these things with. We just needed different processes.”

The high euthanasia rate was not the result of malevolence, Tomlinson said. “These were good people. They didn’t hate animals. They love animals. It’s just there were all these antiquated policies bent toward animals being vermin and nuisances and disease-spreading.” The view that “any animal not in a home was a public health threat” was outdated, she said. “We had a wonderful facility we could do all these things with. We just needed different processes.”

She quickly moved to reform policies and practices by developing a Save-a-Pet program for the city, but it wasn’t easy. “Somehow we got into a war we didn’t ask for,” she said. One problem: animal welfare groups with different philosophies, like PETA and PAWS were at cross purposes.

Tomlinson found programs that worked, and “cherry- picked” best practices in her Save-a-Pet plan. In researching the issue, Tomlinson found that some cities that had adopted no-kill policies often resorted to simply warehousing animals. “Yeah, you’re not killing them, but you’re giving them to these groups that don’t have any capacity to have programs so they’re just being warehoused in strip malls,” she said. For her, that wasn’t a solution.

Stray cats and cat people

Then there were people who attracted large numbers of cats by putting food outside for them. This caused all sorts of problems: rabies, late night noise pollution, and more cats. She said a neighbor had collected 65 cats that way. Tomlinson said there was also a stigma that went along with the practice, both for humans and felines.

Under the old regime, these cats would have been euthanized. But that policy hadn’t worked. Sixty-five cats across the street from the mayor’s house proved it. Tomlinson tackled the essential issue of getting the stray cat population under control as humanely as possible, but she faced opposition from those who viewed these cats as pests. Tomlinson proposed a Trap-Neuter-Release program, which also involved giving the animals five-year vaccinations for rabies. “TNR is the single most effective way to prevent rabies,” Tomlinson said. Nevertheless, it was a contentious process. Getting it approved involved, among other things, “five-hour hearings where experts testified on cat vaccines,” she said.

Tomlinson won the political battle, convincing the ten-member Columbus City Council to go along with a plan for vaccinating cats and releasing them, with exceptions for severely injured or diseased animals. One thing that helped: a grant to fund the comprehensive TNR Program.

Once the animals were spayed, nature took its course, and the stray cat population declined dramatically. Tomlinson said, “(TNR) culled the population,” and allowed the cat people “to come out of the shadows” and be brought into the program. Over time, the population of homeless cats was greatly reduced by predators and “the rough and tumble of being outside.”

Adoptions

The other big issue was adoptions. Developing a comprehensive adoption program took a lot of effort by many partners, both public and private. Tomlinson said animal-save groups were vetted, and had to comply with standards to prevent warehousing.

“We began to promote adoptions,” Tomlinson said. “We had amazing groups that posted for adoption on their social media. I did a lot of PSAs and promoted adoptions for Christmas and summer vacations. City news channels broadcast pets for adoption once a week. We began to adopt out animals in massive numbers.”

The city also offered a low cost spay neuter voucher program for adopted animals

After the program was instituted, the city’s euthanasia rate fell from 80 to 60 percent in just a couple of months, Tomlinson said. And it kept falling. From 2014 through 2016, more than 7,144 animals were adopted in the city. Six years after she’d begun work on the program, the city received recognition, with the award from Harvard and a designation as a no-kill community. “What makes government work best is the drive to do better,” said Harvard official Stephen Goldsmith in announcing the Bright Ideas award.

After the program was instituted, the city’s euthanasia rate fell from 80 to 60 percent in just a couple of months, Tomlinson said. And it kept falling. From 2014 through 2016, more than 7,144 animals were adopted in the city. Six years after she’d begun work on the program, the city received recognition, with the award from Harvard and a designation as a no-kill community. “What makes government work best is the drive to do better,” said Harvard official Stephen Goldsmith in announcing the Bright Ideas award.

“This could not be possible without our many shelter partners: Animal Ark Rescue, Animal SOS, Columbus Animal Care and Control, Harris County Animal Control, Harris County Humane Society, Paws Humane, and the citizens of these two communities and surrounding areas,” Tomlinson told the Ledger-Enquirer in 2017.

Legacy Note: Inn 2019, the year after Tomlinson left office, thanks to the Save-a-Pet program, Columbus went an entire year without euthanizing an animal to make space.

Liked this post? Follow this blog to get more.