Note: Not a damned thing has happened on this issue since I originally posted in February (except for hate crime) so I’m re-posting with a more exasperated headline.

Update: In an article published today, Gov. Kemp said he’s “open” to hate crime legislation, but wouldn’t say he’d sign it–essentially the same message I received from Rep. Mitchell, who met with Kemp on the issue early in the General Assembly session. Nothing has changed.

If Governor Kemp hates crime so much, why doesn’t he hate hate crimes?

By Jonathan Grant

@Brambleman

Brian Kemp hates gangs. In 2018, the self-described “politically incorrect conservative” promised he would “protect Georgia families by crushing street gangs.” Now, his second year in office, the governor has unveiled his anti-gang legislation. One bill, the Nicholas Sheffey Act, would authorize stiffer penalties for gang violence, even though Georgia already has a tough anti-gang statute and Sheffield’s killer was sentenced to life without parole plus 675 years.

Under Kemp’s plan, “In murder cases involving gang activity, defendants would automatically be eligible for the death penalty,” the AJC reported. “The death penalty can already be used in a wide range of cases that could include gang cases, though capital punishment is becoming less common in recent years as life without parole has become more common.”

Indeed, even conservatives argue against the death penalty.

While Kemp seeks to expand the death penalty, the state blocks condemned prisoners from using DNA evidence in their attempts to exonerate themselves. It seems appropriate to also note that his state budget plan slashes public defender budgets by $3 million. As for keeping kids out of gangs, Kemp sees little role for the government, instead calling on churches, community organizations and families to keep kids out of gangs. This focus on punishment rather than prevention seems not just conservative, but reactionary. It pays to be Tough On Crime® in an election year.

But what about hate crimes?

Meanwhile, Kemp has kept quiet about hate crimes, which the FBI defines as a “criminal offense against a person or property motivated in whole or in part by an offender’s bias against a race, religion, disability, sexual orientation, ethnicity, gender, or gender identity.” People of color, Jews, Muslims, women, and LGBTQ folk are common victims of such crimes.

Georgia is one of four states without a hate crimes law—a measure that metes out extra punishment for crimes fueled by prejudice—but there is currently a hate crimes meaure in the General Assembly. House Bill 426 passed the House last year and now languishes in the Senate.

Last year there were five such states, but Indiana-–home to homophobic Mike Pence–recently enacted a hate crimes law, so now Georgia holds the distinction of being a “haters gonna hate” state along with only Arkansas, South Carolina, and Wyoming, where a young gay man, Matthew Shepard, was murdered in 1998.

Shepard’s murder received widespread attention and his killers were convicted and given life sentences, but the case was not treated as a hate crime. A month after Shepard’s murder, the Human Rights Campaign conducted a poll showing 56 percent of Americans supported the Hate Crimes Prevention Act. A decade later, Congress passed federal hate-crimes legislation named in his honor. His deeply conservative home state has never passed a similar bill.

In Georgia, hate crimes are on the rise. WTVM in Columbus recently reported on a study showing that the state had the second highest rate of increase of hate crimes in the nation.

But things are tough all over. The FBI recently reported that “attacks motivated by bias or prejudice reached a 16-year high in 2018 … with a significant upswing in violence against Latinos outpacing a drop in assaults targeting Muslims and Arab-Americans.”

Many people point to President Trump’s anti-immigrant rhetoric as a contributing factor to the problem. Kemp’s campaign pledge to use his pickup to haul “criminal illegals” back where they came from probably wasn’t helpful either, but it was par for the Republican course. In 2018, one of his GOP opponents drove around in a “deportation bus”—until it broke down. In any case, it’s not surprising that hate crimes against Latinos have risen in the past few years.

According to the FBI, such crimes against property were down nationwide, but physical assaults against people were up: 61 percent of the 7,120 incidents were classified as hate crimes. But here’s the thing: State and local police forces are not required to report hate crimes to the FBI, and many cities and some entire states don’t collect or report data. So, we don’t know the full extent of the problem. This can be especially true in states like Wyoming, as the Cheynne Star Tribune recently noted.

Some History

Georgia has passed hate crimes bills in the past. They just haven’t worked. Another attempt, in 2018, was dead on arrival, but HB 426 still has a chance of passage.

Georgia has passed hate crimes bills in the past. They just haven’t worked. Another attempt, in 2018, was dead on arrival, but HB 426 still has a chance of passage.

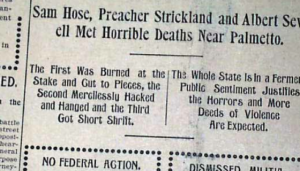

Back in the day, Georgia had an antilynching statute on the books:

When Governor (William) Northen pushed an antilynching bill through the legislature in 1893, Georgia was one of only two states to have such a law on the books. It authorized sheriffs to deputize persons to protect prisoners and made failure to do so a misdemeanor. This law accomplished little or nothing, however.—The Way It Was in the South: The Black Experience in Georgia

The law didn’t work, and probably wasn’t intended to—just window-dressing for “The New South.” Prosecutions for lynching were virtually nonexistent.

While it failed to pass antilynching legislation to protect its most vulnerable citizens in the century after the Civil War, Congress has passed several hate-crimes bills over the past five decades.

During the civil rights era, Congress passed a bill that made it a crime “to use, or threaten to use, force to willfully interfere with any person because of race, color, religion, or national origin.” Two decades later, family status and disabilities were added to protections. During President Obama’s first year in office, he signed the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act, providing protections for people based on gender, gender identity, and sexual orientation.

In 2000, more than a century after Gov. Northen’s all-show-and-no-go antilynching measure, the Georgia General Assembly passed a hate crimes bill. During the waning years of the General Assembly’s Democratic majority, then-Sen. Vincent Fort introduced Senate Bill 390, the “Anti-domestic Terrorism Act,” drawn up to fight hate crimes by providing:

… enhanced sentences in any case in which the judge imposing the sentence determines beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant intentionally selected any victim or any property as the object of the offense because of the actual or perceived race, color, religion, national origin, ancestry, ethnicity, gender, disability, or sexual orientation of the victim or any person associated with the victim, or with the property which is the object of the offense.

The bill passed the Senate, 30-23. Sen. Sonny Perdue, two years away from being elected governor, voted against it. In the House, after some parliamentary wrangling, a substitute bill passed by a wide margin, 117-49. But there was a problem. The House had gutted Fort’s bill by removing the protected classes of victim. The law did not specify any “hatees.” The Senate agreed to the changes and it was signed into law by Gov. Roy Barnes. The law was challenged in 2004, and the Georgia Supreme Court unanimously ruled that it was unconstitutionally vague—in essence, meaningless.

That year, 76 percent of Georgians approved a state Constitutional amendment outlawing gay marriage. In the same election, Republicans won complete control of state government. Fixing the hate crimes law wasn’t on their agenda. Instead, they moved to institute restrictive Photo ID requirements for voters to ensure they kept power, and for many years hate crimes disappeared as a thing among Georgia’s political leaders.

Which way are we going?

In 2015, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down bans such as Georgia’s on gay marriage. However, the next year, President Donald Trump and homophobic Vice President Mike Pence took office. The Obama Administration’s friendliness was replaced with hostility. Trump banned transgender military service. The Justice Department argues that gay workers aren’t covered by civil rights laws. With the Federalist Society furnishing the nominees and a Republican Senate voting them in, homophobia is no longer a bar to being appointed to the federal judiciary. The Human Rights campaign has published a timeline of the Trump Administration’s ugliness.

In 2015, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down bans such as Georgia’s on gay marriage. However, the next year, President Donald Trump and homophobic Vice President Mike Pence took office. The Obama Administration’s friendliness was replaced with hostility. Trump banned transgender military service. The Justice Department argues that gay workers aren’t covered by civil rights laws. With the Federalist Society furnishing the nominees and a Republican Senate voting them in, homophobia is no longer a bar to being appointed to the federal judiciary. The Human Rights campaign has published a timeline of the Trump Administration’s ugliness.

If you believe, in line with Dr. Martin Luther King’s thinking, “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice,” then Trump and his allies are on the wrong side of history, and equality and equity will prevail. But just to be sure, you should be working in the 2020 elections.

Notwithstanding the regressive politics of Trumpism, there has been progress on the state and local level, though sometimes the results are a mixed bag. Indiana’s new hate crimes law stops short of explicitly providing protections base on age, sex, and gender identity. Similarly, Alabama’s law doesn’t cover its LGBTQ citizens. Hate crimes legislation has been introduced by South Carolina’s Jewish legislator—yes, singular—but it hasn’t progressed.

The Anti-Defamation League has compiled a state-by-state guide on these laws.

The purpling of Georgia and new initiatives

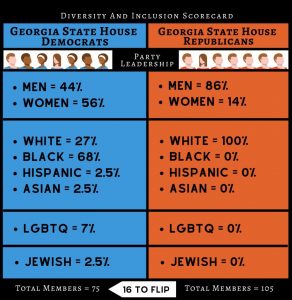

Georgia’s increasingly diverse population has had a profound effect on the Democratic Party. Voters across Metro Atlanta have elected several LGBTQ legislators. Stephe Koontz, a trans woman, serves on Doraville’s City Council. Many local governments have passed or are moving toward passage of inclusive, anti-discrimination ordinances.

This trend has also turned Georgia into a swing state, and Metro Atlanta’s sprawling suburbs have turned royal blue. This has had an effect on Republicans (besides vowing to come up with millions of dollars to fight off Democratic challenges). Significantly, recent attempts to pass hate-crimes legislation has been led by Republicans facing difficult re-election contests, thanks to demographics and Trump’s unpopularity among educated voters.

In 2018, such a bill was sponsored by Republican legislator Meagan Hanson, who represented a swing district in Brookhaven and Sandy Springs.

Alas, it was DOA. House Bill 660, the Atlanta Jewish Times reported, “endorsed by the Anti-Defamation League and the Coalition for a Hate-Free Georgia, never got out of House Judiciary Non-Civil Committee. It had a hearing Feb. 13 before a subcommittee chairman who took the view that the measure was unnecessary because all crimes are hate crimes.”

Hanson’s bill included protections based on sexual orientation and gender identity. It also had detailed sections requiring the state to train law enforcement personnel how to deal with and report hate crimes.

Not only did the bill go nowhere, but Hanson was defeated that fall by Democrat Matthew Wilson, a gay man. This was one of a dozen House seats Democrats gained in 2018, and they set their sights on retaking the chamber after nearly two decades out of power.

In 2019, HB 426, a bipartisan measure, was sponsored by Republican Chuck Efstration and co-sponsored by two other Republicans, Deborah Silcox and Ron Stephens. All of their seats are top targets in Democrats’ takeover plans.

Unlike Hanson’s bill, HB 426 doesn’t include gender identity as a victim class. That’s a flaw: Transgender people, especially black trans people, are often targeted for violence based on their identity. And while some supporters argue that the bill somehow covers crimes against trans people, including gender identity as a class would make protections—and legislative intent—more obvious. The bill also has no requirements for training or reporting. Setting up reporting requirements is important because tracking of bias crimes is so spotty.

Nevertheless, HB 426 moved forward, passing the House with five votes to spare, 96-64, in time to be considered in the Senate. But that’s where it hit a wall. More specifically, a Stone wall. “Senate Judiciary Chairman Jesse Stone, R-Waynesboro, said he believes victims should have an equal chance at justice and isn’t sure that increased penalties for crimes against certain people is the best way to go,” the AJC reported.

Both Stone and the unnamed legislator who said “all crimes are hate crimes,” seem to be ignoring the threat posed by the rise of white supremacist ideology. (Or is it just that Republicans hate regulation?) Stone has also decided against seeking re-election, which may make him immune to calls for action.

Along with increased attacks on immigrants, Jews, people of color, and LGBTQ persons, violent white supremacy is a destabilizing force for society. Such violence isn’t just a crime problem—it is, as Fort aptly noted in 2000, a domestic terrorism problem. Put in that context, it should be considered just as dangerous as gang activity—or more so. People are already talking about civil war if the fall elections don’t go their way. The heavily armed lockdown protesters at state Capitols are an ominous sign of our possible near-term future. Rather than creating “special rights” for certain people, hate crime laws are better viewed as dealing with a special class of offender. Like a gang member, if that helps.

On a more positive note, consider LaGrange College professor John Tures’ argument. He believes hate crime laws may help reduce all crimes:

For the murder rate, you’ll find states lacking a hate crimes law sporting a statistic of 5.08 killings per 100,000 residents. That drops to a murder rate of 3.95 homicides per 100,000 residents for states prudent enough to pass a hate crimes law. For aggravated assaults, it’s a similar disparity in favor of states with hate crimes laws.

Where are we now, and why don’t legislators pass a good bill?

HB 426 stalled in the Senate last year (and is still stalled). In November, Georgia’s Legislative Black Caucus picked up the torch and pushed for passage following an alleged plot in Gainesville by a teenager to attack a black church. There’s been little movement this year, although last week, black faith leaders held a news conference at the Capitol to push the bill. Project Q Atlanta reported that Reps. Billy Mitchell and Karen Bennett of DeKalb County were scheduled to meet the governor today to solicit his support for passage. Since Kemp has been relatively silent on the issue, we’ll have to wait and see what happens.

Still, HB 426’s failure to address crimes based on the victim’s gender identity—and its failure to set up training standards and reporting requirements for law enforcement—make passage in its present form something of a pyrrhic victory. If Kemp really wants to be tough on crime, he could insist that these issues be addressed. As long as we’re doing it, why not do it right?

Perhaps the white vigilantes’ killing of black Glynn County jogger Ahmaud Arbery in February–along with the subsequent cover-up by area prosecutors—will create some energy to overcome legislative inertia on the issue. But so far, the sound of crickets from the governor.

Liked this post? Follow this blog to get more.